It's in the signature.

We were contacted by a worried reader: he had found 2 seemingly identical µTorrent executables, with valid digital signatures, but different cryptographic hashes. With CCLeaner's compromise in mind, this reader wanted to know why these 2 executables were different.

I took a look at the 2 executables submitted by our reader: executable 1 and executable 2.

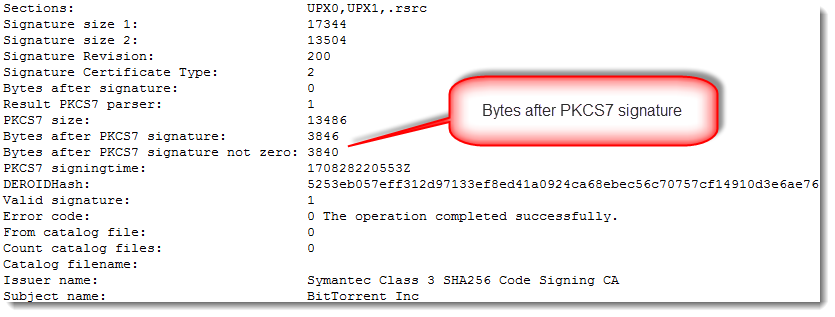

Taking a look with my AnalyzePESig tool, I discovered that both executables have a valid signature. Both signatures have the same structure (DEROIDHashes are identical), and the thumbprints of all involved certificates match.

The DEROIDHash is something I created to analyze AuthentiCode signatures with my AnalyzePESig tool: it's the MD5 hash of a list of the DER data types and OID numbers used in the signature. Signatures with the same order of data types and same order of OIDs, will have the same DEROIDHash.

There is however, something with these signatures that I noticed:

There is data appended after the AuthentiCode signatures (bytes after PKCS7 signature). With normal AuthentiCode signatures, there are at most a few NULL bytes added as padding. Finding something else than NULL bytes after the PKCS7 signature means that something was added: more on this later.

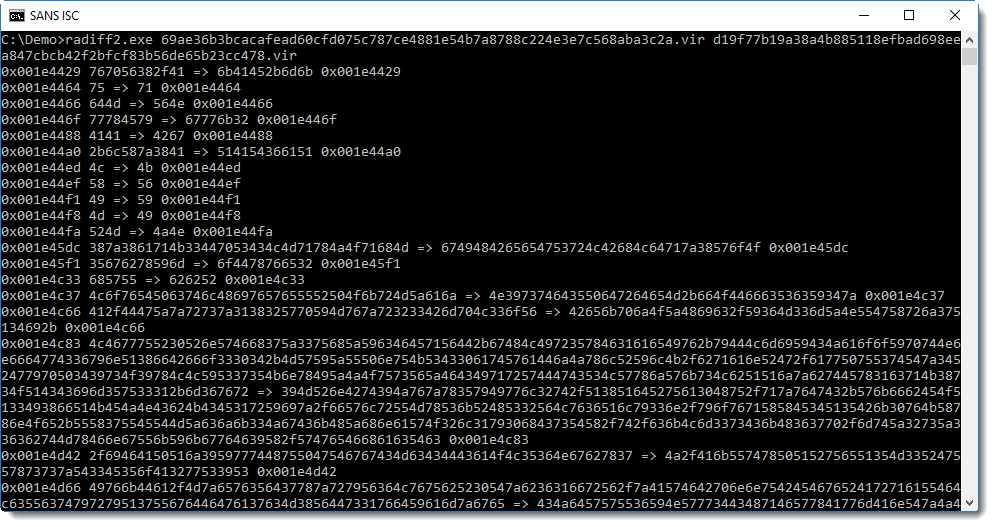

When I compare these 2 files with Radare2, I see that they are mostly identical (they have the same size: 1985984 bytes):

The first difference between the 2 files is at position 0x001E4429 or 1983529. With a file size of 1985984, it means that the files are mostly identical.

So what is the difference?

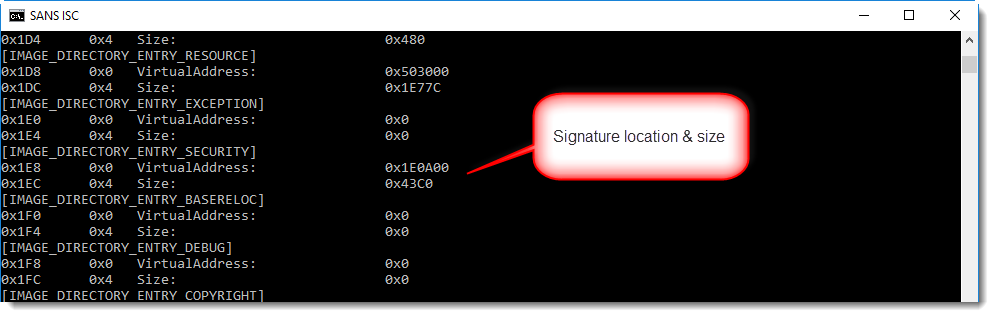

With a signed executable, the signature can be found at the end of the file (unless debug data or other data has been appended). With pecheck.py, we can see that the digital signature starts at position 0x1E0A00: hence the difference occurs somewhere inside the digital signature, because the first difference starts at 0x001E4429.

1985984 (the file size) minus 1983529 (the first difference) is 2455. That's smaller than the size of the data appended after the PKCS7 signature (3846 bytes). Conclusion: in both files, the executable (code, resources, ...) and the signature are identical. It's only part of the appended data that is different.

Before we continue, there are some things to know about AuthentiCode signatures:

- The signature signs a cryptographic hash of the executable

- This cryptographic hash is not the hash of the complete file: the bytes that make up the signature itself (and the pointer to and size of the signature) are excluded when the hash is calculated

- This means that data can be injected in the digital signature directory without invalidating the signature

It has been known for many years that data can be injected after the digital signature, without invalidating the signature: it's something I observed almost 10 years ago, and I'm sure I was not the first.

Microsoft wanted to prevent this with patch MS13-098, but ultimately did not enforce this.

Several software authors use this "feature" in signed installation programs to include data, like licensing data.

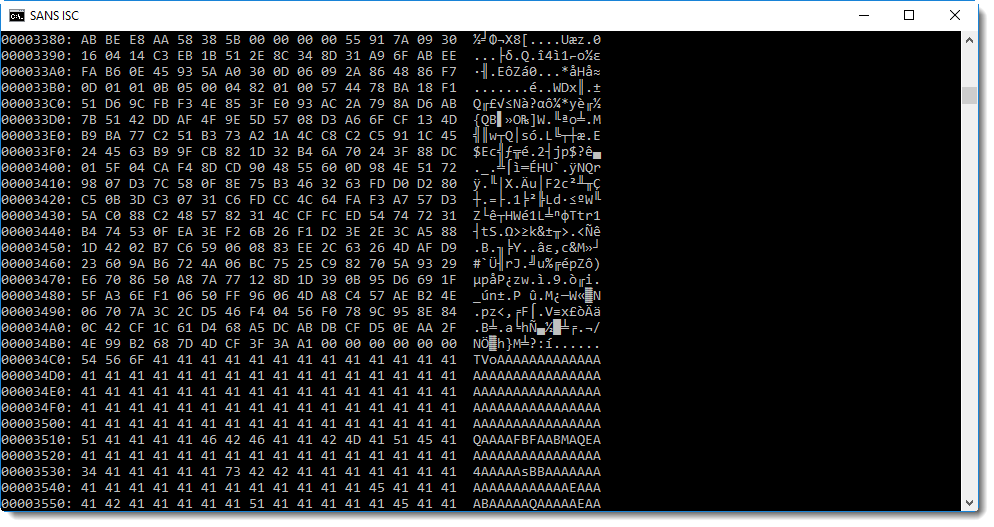

With all this information it's time to look at the data appended after the signature:

You will probably recognize this: BASE64 encoded data. And maybe you'll even know that TV... means MZ..., hence a PE file.

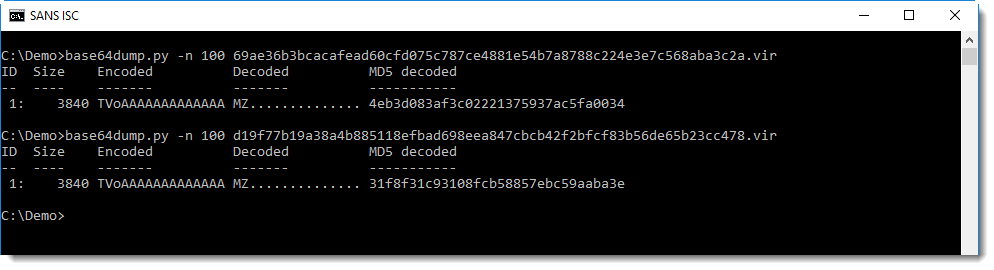

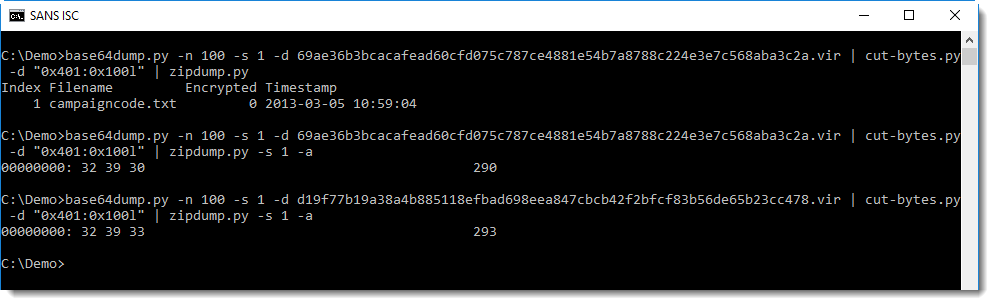

base64dump.py confirms this:

Both executables have BASE64 data injected inside the signature: this is another PE file, that is different for both files.

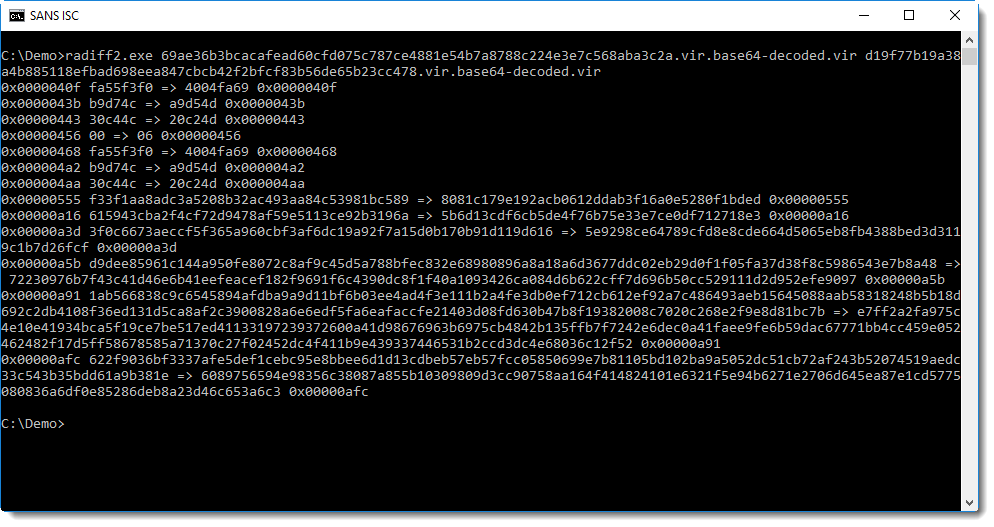

OK, now let's compare these 2 embedded executables:

The first difference is at position 0x40F. That is in the code section (.text) of the executable:

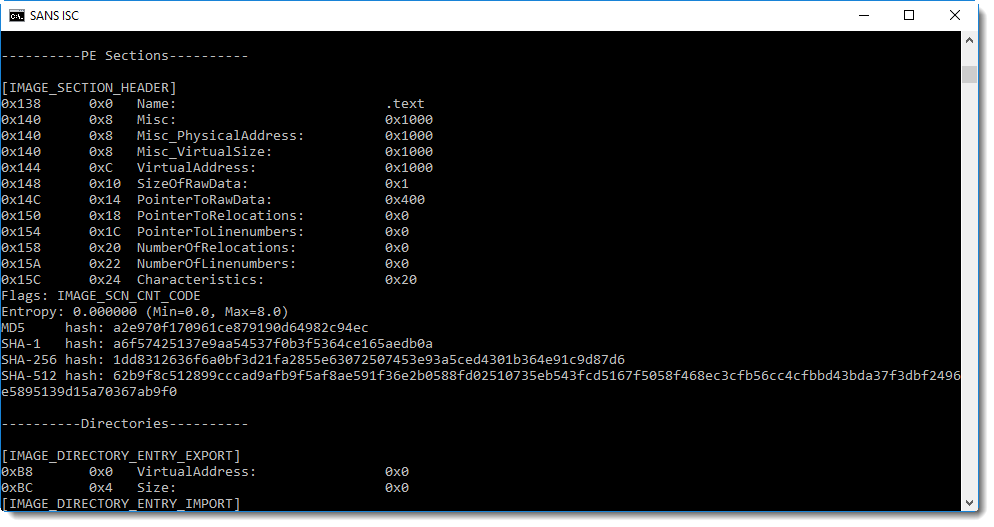

From the sections here we can see that this is not your typical executable: there is only one section (.text) that is not executable and contains just one byte.

Time to take a look at this section:

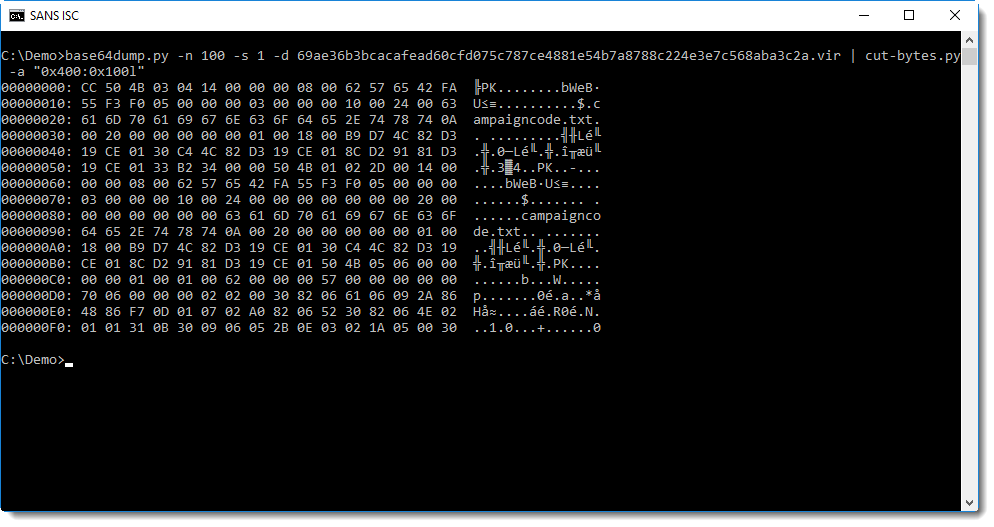

So the first byte in the .text section is CC. Next we see PK: that's the header of a ZIP file!

Let's check if it is indeed a valid ZIP file with zipdump.py:

It's indeed a ZIP file, containing a single text file: campaigncode.txt. This text file contains the number (text) 290 in the first file and 293 in the second file.

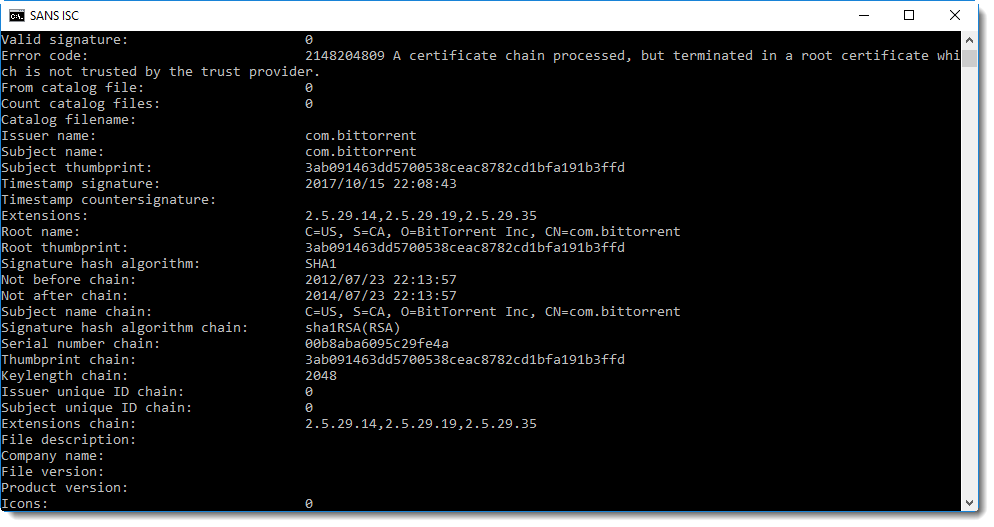

These embedded executables are signed with a self-signed certificate:

Time to make a final conclusion: these executables are identical, except for a campaign code (a number). It's something that the developers did already several years ago, I looked at a µTorrent executable of a couple of years ago and found campaign code 170 (embedded in the same manner).

The method to embed the campaign code is complex: a text file inside a ZIP file inside a PE file, BASE64 encoded and injected in the digital signature of a PE file.

Why is it so complex? I don't know, maybe they use this method to prevent spoofing: by signing the embedded PE file (self-signed certificate), the embedded campaign code is actually signed too. But it would be signed too if it was just embedded as a resource in the signed µTorrent executable (remark that the µTorrent files are signed with a commercial code signing certificate (BitTorrent Inc) and the embedded PE file with a self-signed certificate (com.bittorent)).

Please post a comment if you have an idea why this method to embed a campaign code is used.

Didier Stevens

Microsoft MVP Consumer Security

blog.DidierStevens.com DidierStevensLabs.com

Peeking into .msg files

Readers often submit malware samples, and sometimes the complete email with attachment. For example exported from Outlook, as a .msg file.

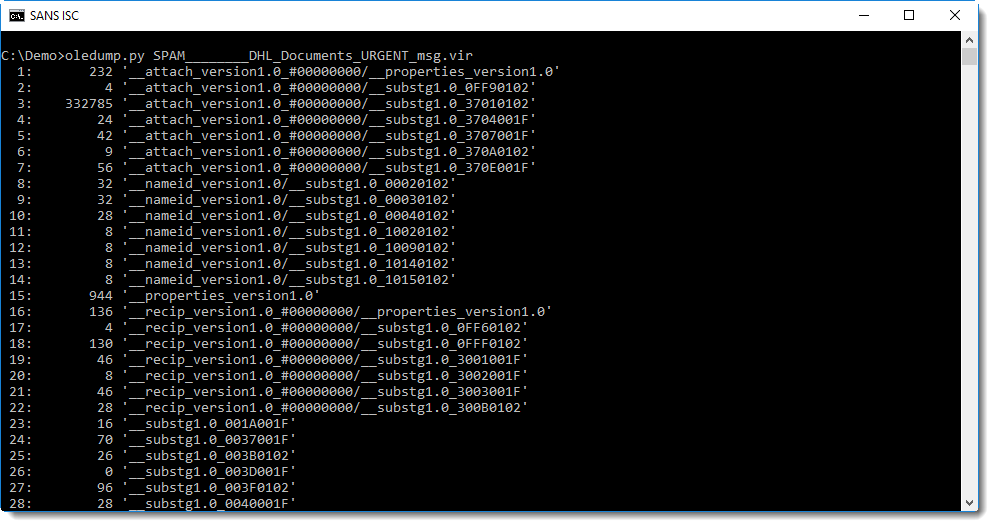

Did you know that .msg files use the Compound File Binary Format (what I like to call OLE files), and can be analysed with oledump?

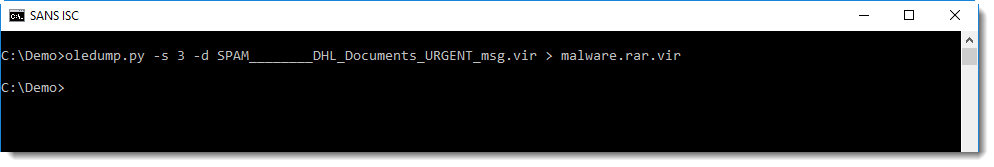

Reader Carlos Almeida submitted a .msg file with malicious .rar attachment.

I'm not that familiar with .msg file intricacies, but by looking at the stream names and sizes, I can often find what I'm looing for:

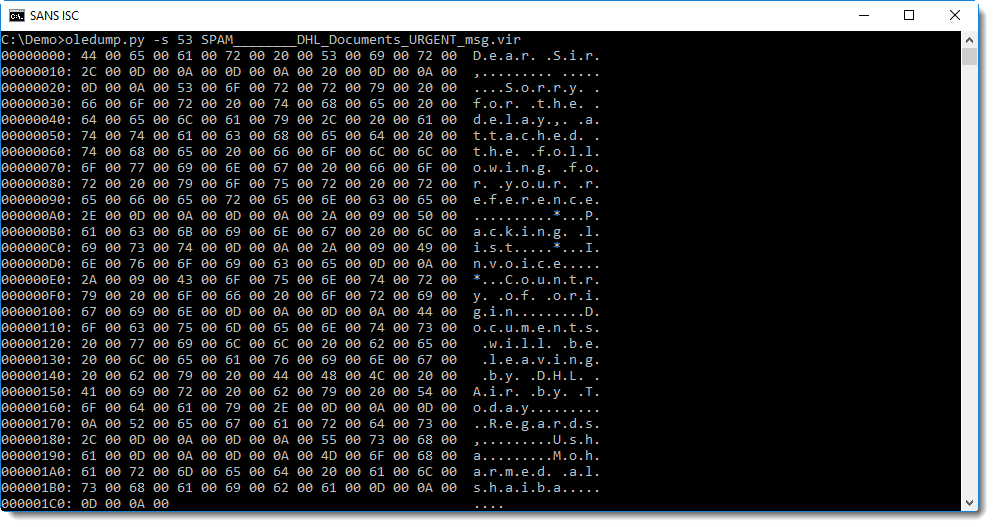

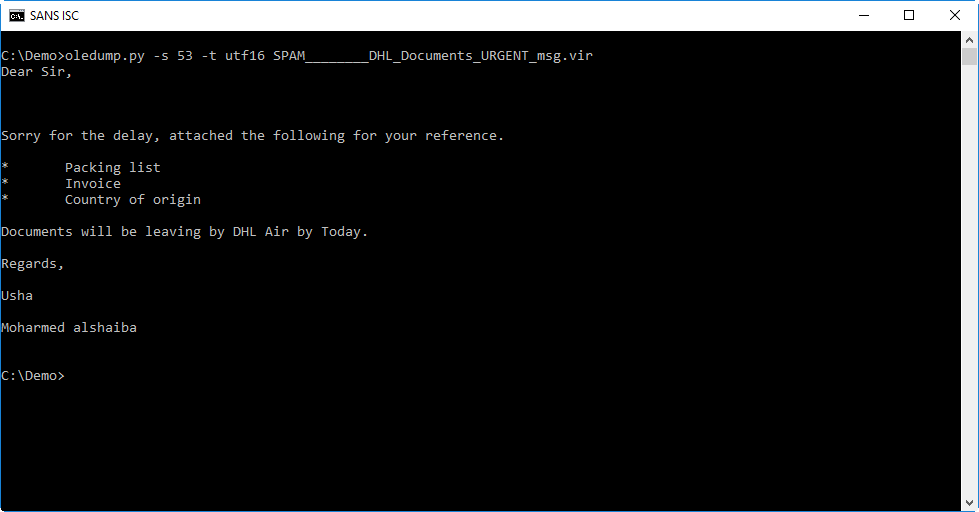

Stream 53 seems to contain the message:

From this hex-ascii dump, you can probably guess that the message is stored in UNICODE format. We can use option -t (translate) of oledump to decode it as UTF-16:

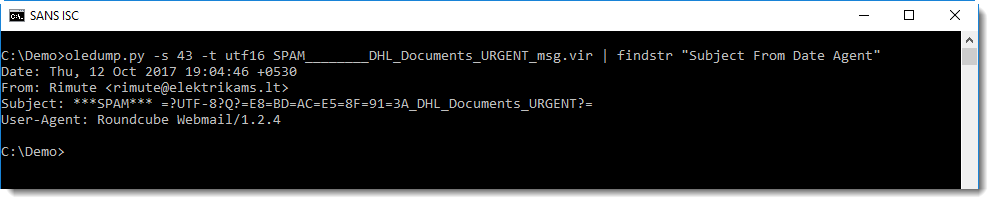

Stream 43 contains the headers. I don't want to disclose private information like our reader's email address, so I grepped for some headers that I can disclose:

The Subject header is encoded according to RFC1342 because the subject contains non-ASCII characters. It decodes to this:

These are chinese characters that seem to mean the same as FW: (forwarding).

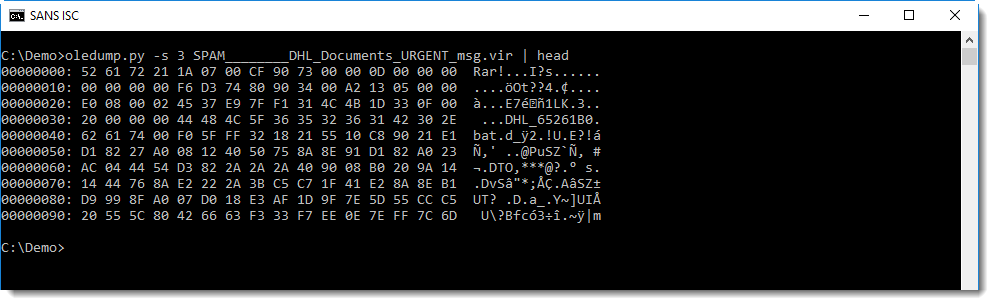

Stream 3 contains the attachment:

You can see it's a RAR file.

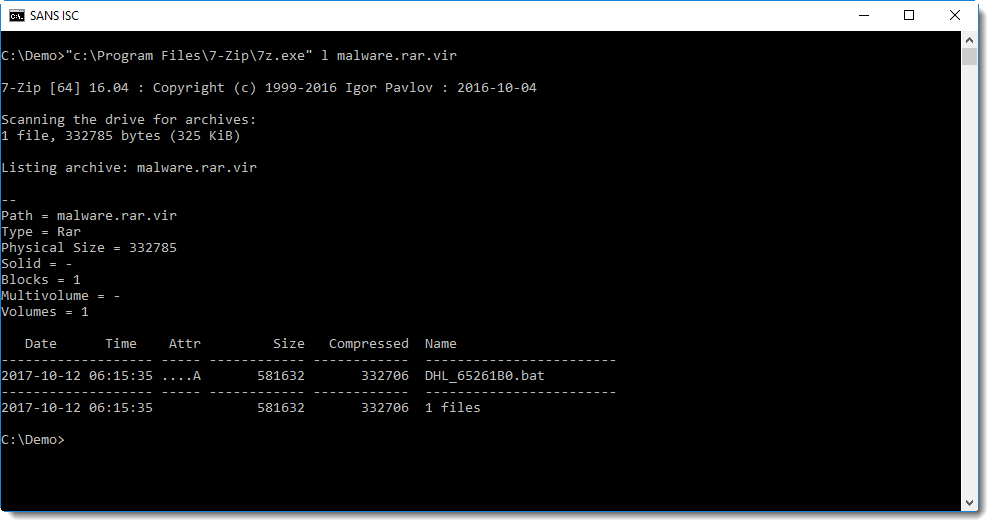

I use 7zip to look into it, and it should be possible to do this without writing the file to disk, by just piping the data into 7zip (options -si and -so can help with piping). But unfortunately, I got errors trying this and resigned to saving it to disk:

It contains an unusually large .bat file:

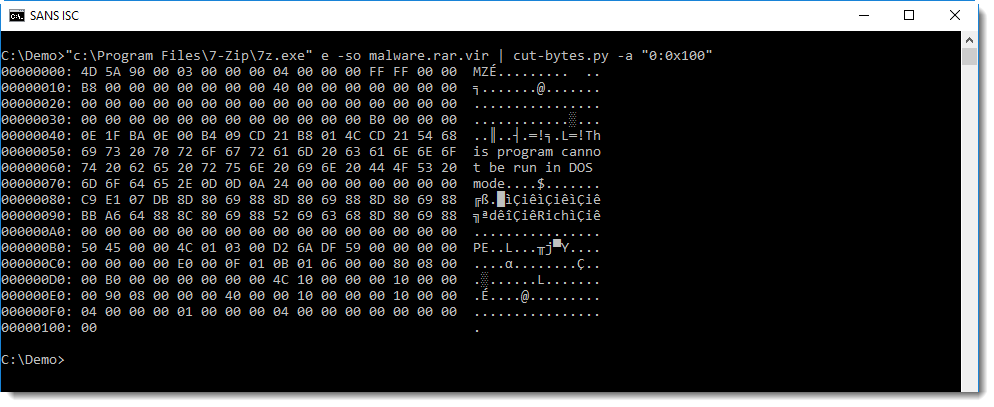

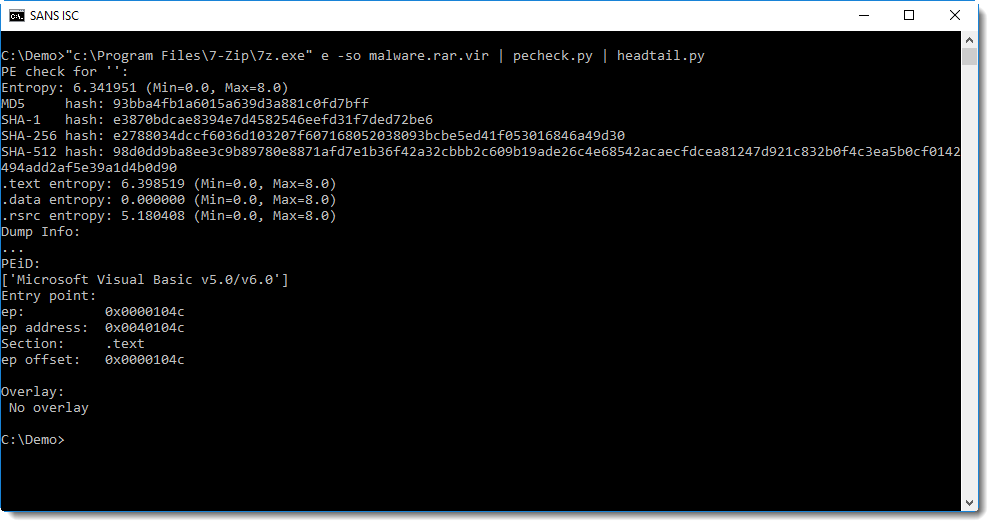

It's actually a PE file:

This looks to be a VB6 executable (from the PEiD signature), I should dig up my VB6 decompiler and try to take a closer look.

Of course, it's malware.

Didier Stevens

Microsoft MVP Consumer Security

blog.DidierStevens.com DidierStevensLabs.com

Comments