The Mirai Botnet: A Look Back and Ahead At What's Next

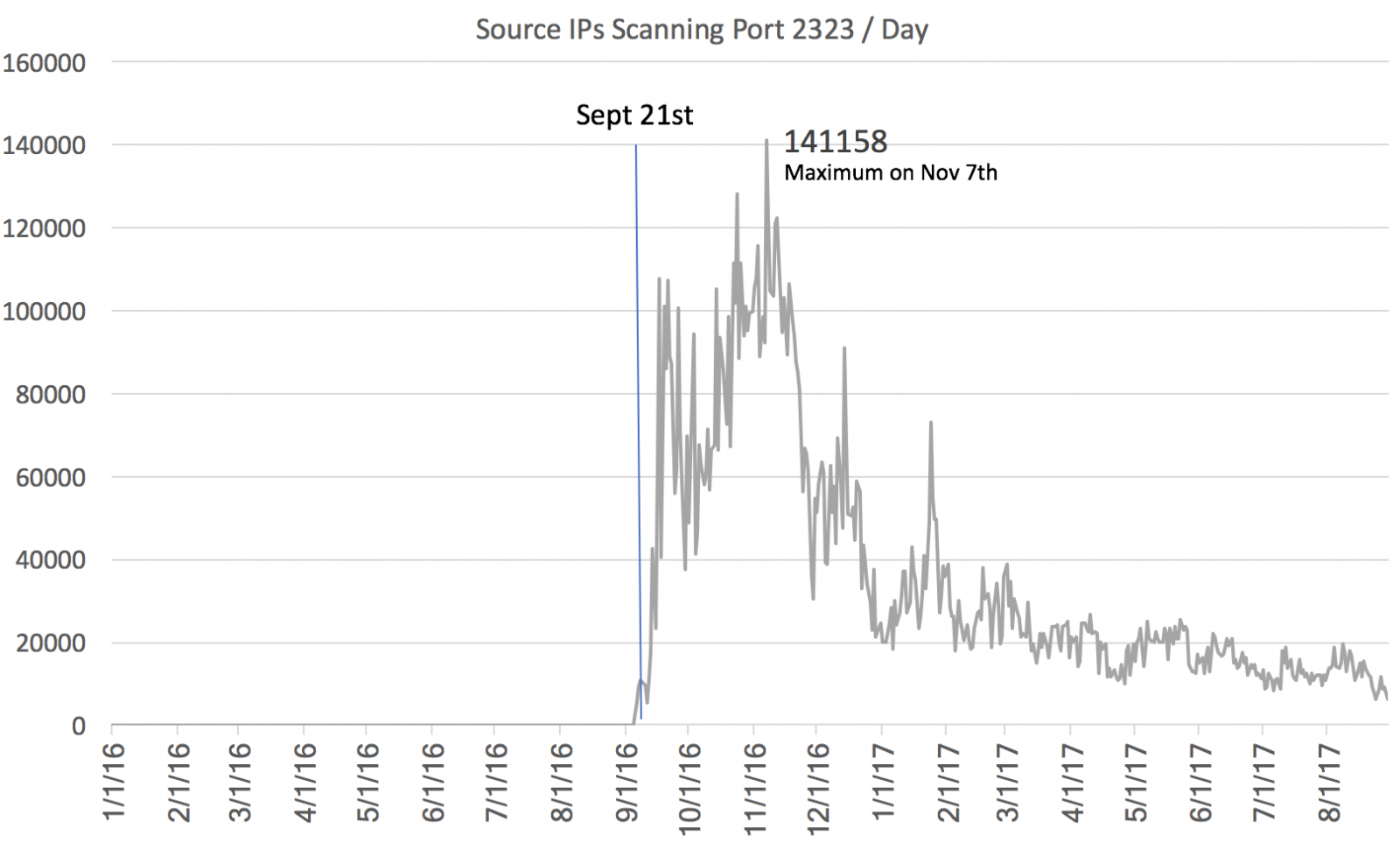

It is a bit hard to nail down when the Mirai botnet really started. I usually use scans for port 2323 and the use of the password "xc3511" as an indicator. But of course, that isn't perfect. The very first scan using the password "xc3511" was detected by our sensor on February 26th, 2016, well ahead of Mirai. This scan hit a number of our sensors via ssh. At the time we did not collect telnet brute force attempts. Oddly enough, it was a singular scan from one IP address (185.106.94.136) . Starting August 9th, 2016, we do see daily scans for the password xc3511 at a low level until they increase significantly around September 21st, which is probably the best date to identify as the outbreak of what we now call Mirai. I will use "Mirai" to identify the family of aggressive telnet scanning bots. It includes a wide range of varieties that all pretty much do the same thing: Scan for systems with telnet exposed (not just on port 23) and then trying to log in using a default password.

Figure 1: Port 2323 Scanning for 2016.

One of the first questions that keep coming up is how many hosts were or still are infected with Mirai. A back of the envelope calculation can be done by looking at the current rate of these scans. An average IP address will be hit once every 10 minutes. In my tests, I found that an infected system can scan about 200 IPs per second. To scan the entire internet, it will take an infected system about 200 days (accounting for the fact that Mirai does not scan about 20% of the IP address space). So to be hit about once every 10 minutes, we need only about 30,000 infected systems. This is likely a low estimate. I have seen a lot of Mirai connection attempts fail because the scanning system isn't responding in time, likely because it is not able to keep up with the scans. For port 23 scans, we do see around 100-150,000 sources each day. This is not just Mirai, but other bots as well. Port 2323 only sees around 5-10,000 sources per day. These are likely remnants of the original Mirai versions. Later versions did not use port 2323 as much as earlier versions. So a reasonable estimate of infected systems is likely in the "more than 100,000" range.

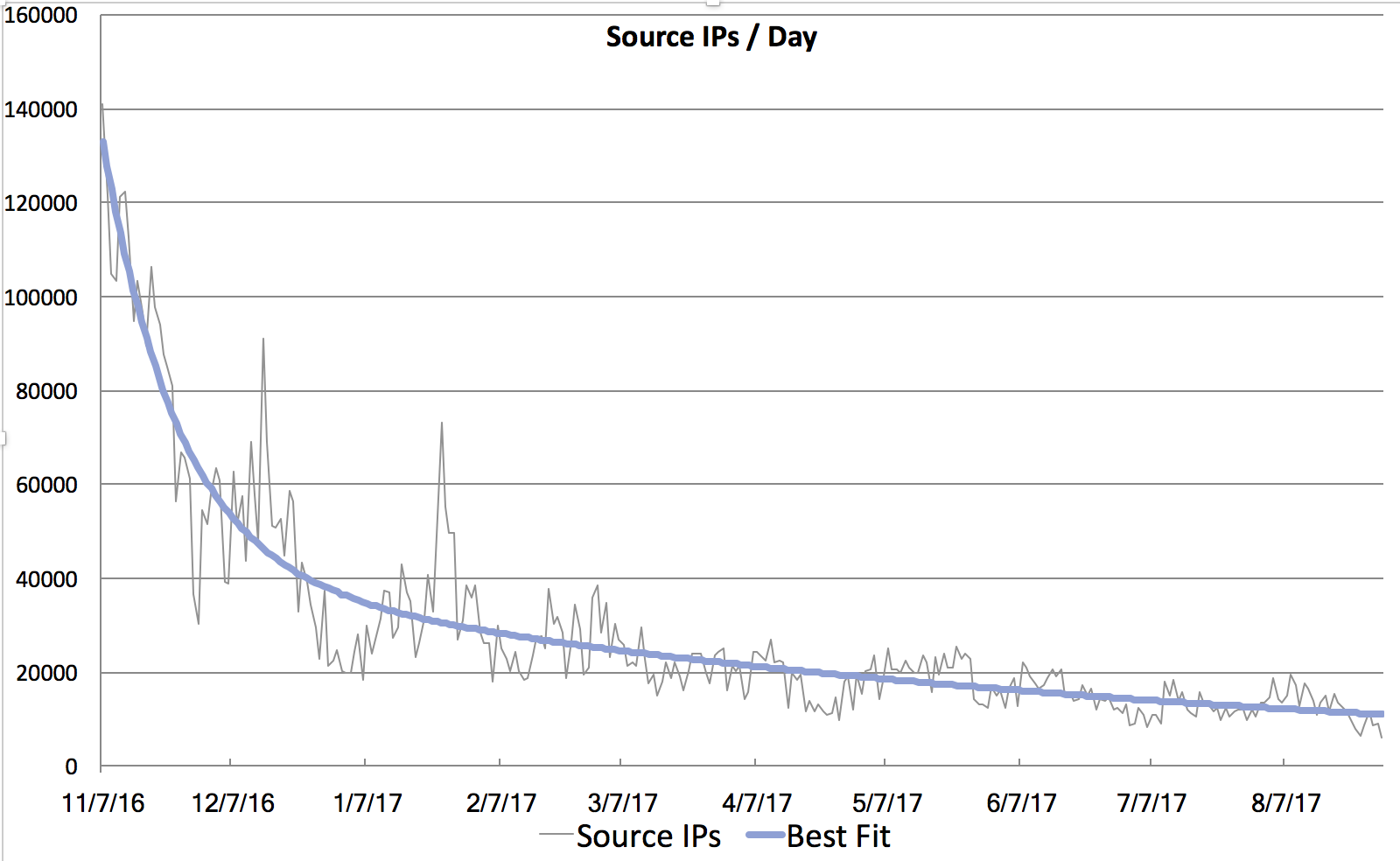

Figure 2: Decay of port 2323 scans and best fit.

Now the next question is: "How long will all this last". I took a look a the port 2323 traffic, to see how it decayed over the last year. Like I have seen in prior bot outbreaks all the way back to Nimda/CodeRed, the decay is best matched using two components: A "fast part" of systems that are patched relatively fast, and a "slow" part of systems that take much longer to fix. For SQL Slammer, for example, the "fast" part was patched in a few hours, while the "slow" part was patched "never". For Mirai, the "fast" decay has a half life of 12 days, which is still pretty slow. The "slow" part has a half life of 150 days, and 1/3 of infected systems are part of the "slow" curve. The result: Mirai is going to stick with us for a few more years. There are many efforts underway to reach out to infected systems and to protect them. But for Mirai, these efforts appear to have reached a point of diminishing returns. Unlike SQL Slammer, Mirai does not affect the host network enough to force a fix, and the fix isn't all that easy (often there is no simple "patch". And the password can not be changed by the user).

A system is only "removed" from the infected pool if it is patched, retired or placed behind a firewall. A system that is rebooted will likely get infected immediatly so we do not have to account for them. The is possibly also a component of new systems connected to the internet. I did not account for them, but they would become part of either the short or long "half-life" component and just increase the amplitude of either. I will try and run a simulation for that as well later.

So what is next?

Mirai and related bots/worms will stay around for the foreseeable future. There is no reason to believe that all backdoor passwords (aka "Support Passwords") have been found. Just last week news broke about such passwords in some Arris DSL modems. Exploiting these passwords is too easy and there isn't much that can be done by the user to protect the device. These are often not passwords that the user can change. In some cases, a firewall may work, unless the firewall itself is vulnerable. A lot of attention was paid to security camera DVRs and IP cameras, but Mirai infects pretty much any Linux based device with guessable telnet password. SSH will not help either. SSH is as vulnerable to default passwords as telnet. Mirai itself doesn't scan for ssh, but other bots do and have done so for a long time. In the end, this is something that has to be fixed by the manufacturer of these devices, not by the end user. The end user may be able to help by stop buying vulnerable devices, but then again, there isn't an easy way for the end user to tell. Maybe some kind of "security seal" that indicates that the device did go through a basic pentest and will provide security updates for a specific number of years will help. But Mirai vulnerable devices are likely still sold today, and due to a large variety of brand names reselling essentially the same device, it is hard to tell if a device is vulnerable or not.

---

Johannes B. Ullrich, Ph.D., Dean of Research, SANS Technology Institute

STI|Twitter|

| Application Security: Securing Web Apps, APIs, and Microservices | Orlando | Mar 29th - Apr 3rd 2026 |

Comments