Over 20 thousand servers have their iLO interfaces exposed to the internet, many with outdated and vulnerable versions of FW

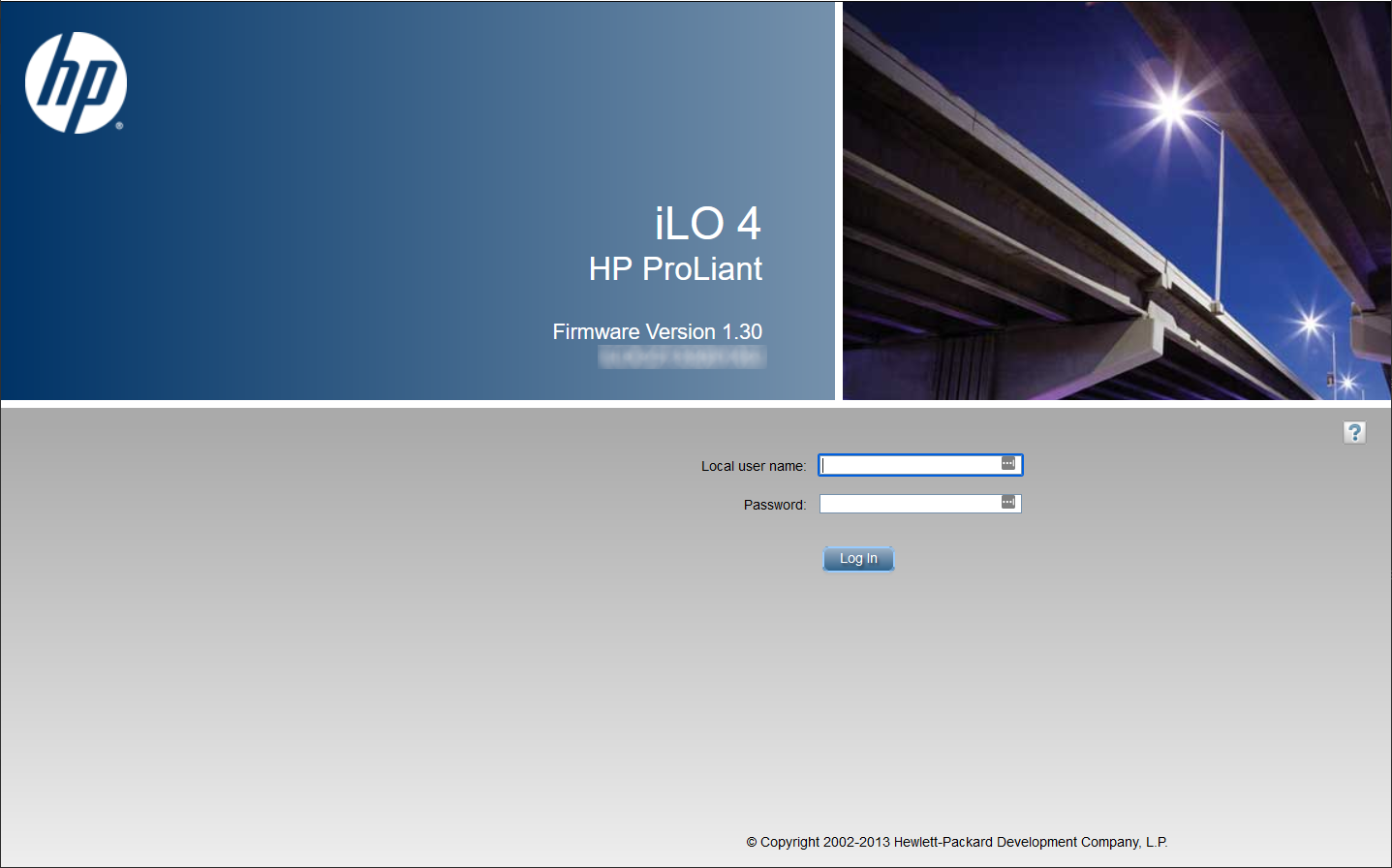

Integrated Lights-Out (iLO) is a low-level server management system intended for out-of-band configuration, which is embedded by Hewlett-Packard Enterprise on some of their servers[1]. Besides its use for maintenance, it is often used by administrators for an emergency access to the server when everything "above it" (hypervisor or OS) fails and/or is unreachable. Since these kinds of platforms/interfaces are quite sensitive from the security standpoint, access to them should always be limited to relevant administrator groups only and their firmware should always be kept up to date.

About a month ago, I came across an analysis of interesting rootkit, which “hid” in the iLO platform[2]. This enabled it to interact with the infected system on a very low level. Since the iLO offers a web-based interface and the text of the analysis also made an allusion to multiple vulnerabilities that were historically discovered in it, it got me thinking on less sophisticated attacks that might target the platform. If remote attackers were able to get access to an iLO, they would basically have full control over the target server. This would certainly pose an issue on local networks, but would be much worse if any iLOs were accessible online and attackers might compromise them over the internet.

Given the aforementioned sensitivity of this interface, you wouldn’t steal a car…I mean expose your iLO to the internet, would you? Especially if HP explicitly says not to do so in their official documentation…[3]

Unfortunately, it seems that a not insignificant number of IT specialists were less security-minded than was optimal and decided they would (expose iLOs on their servers to the internet, that is, not steal a car… I hope).

But back to the beginning.

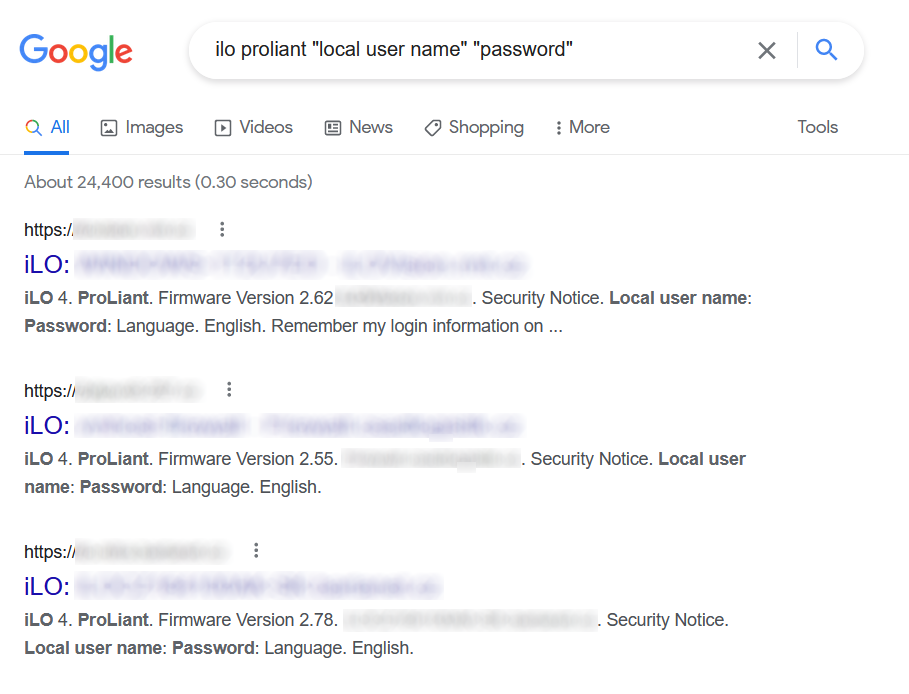

To determine whether any iLOs were "out there", I first looked for an image of the iLO login page (Google Image search for “ilo login page” returned plenty of relevant results) and then constructed the following search string which I thought might give me some idea of whether Google indexed any such pages.

ilo proliant "local user name" "password"

To my surprise, this search yielded over 24 thousand results.

A quick glance through the results seemed to indicate that they really represented internet-exposed iLOs, however the number seemed to be excessive to me, so I turned to Shodan for a “second opinion”.

In simple terms, Shodan periodically scans the entire public IP space for open ports, gathers data returned on those ports, and enables one to search through it in multiple different ways. This gives one a lot of data to play with, but since Shodan does not (primarily) index contents of websites, searching through it is usually not as straightforward as using Google.

After some initial trial and error, I ended up using mainly appropriate favicon hashes[4] in order to identify publicly exposed iLOs. I’ve managed to identify 5 different favicons that were used by different iterations of iLO (version 2 to the most current version 5) over the years, and an additional search string that would lead to only iLO version 1 results being returned by Shodan. Having covered all main iLO versions, I calculated MurmurHashes[5] for all of favicons, constructed relevant search strings and eliminated false-positives as best I could (you may find the resulting search strings near the end of this article). After I summed up all the results, they came to 22,120 public IPs.

It seemed that Google was not as far of the mark as I had hoped… And a further look at some of the identified FW version numbers made the situation seem even grimmer.

As we alredy mentioned, the HP Integrated Lights-Out platform has gone through 5 different iterations over the years (iLO, iLO 2, iLO3, iLO 4 and iLO 5). And, over time, multiple vulnerabilities were identified and patched in each of them[6]. Some of these vulnerabilities had fairly high CVSS scores, such as the 9.8 rated CVE-2017-12542[7] – a trivial-to-exploit authentication bypass that affected iLO 4 before firmware version 2.53[8].

Yet, the previously mentioned Shodan searches revealed a significant number of iLO 4s with (sometimes much) lower FW version numbers… And the situation was fairly similar for other vulnerabilities as well.

Overall, Shodan searches that I originally ran about two weeks ago returned the following numbers for different iLO iterations:

| iLO 1 | 84 |

| iLO 2 | 567 |

| iLO 3, 4 and 5 (the most common favicon is used in all 3 iLO versions) | 21,469 |

Given the number of internet-exposed iLO interfaces I managed to find, many of which were running out of date/vulnerable versions of firmware (and none of which should be directly accessible from the internet in the first place, since the exposure alone goes against good industry practice and introduces unnecessary risk), I’ve decided to let the international CSIRT community know about my findings before I published them here. About two weeks back, I sent an e-mail to all full member teams of FIRST and TF-CSIRT with the description of the issue and a list of Shodan “dorks” that they might use to check for exposed iLOs in their own constituencies.

It seems that this effort bore at least some fruit since the number of iLOs detected by Shodan has fallen somewhat in the meantime. The number of results returned by Shodan for the same searches at the time of writing is as follows.

| iLO 1 | 83 |

| iLO 2 | 529 |

| iLO 3, 4 and 5 (the most common favicon is used in all 3 iLO versions) | 20,911 |

Although January has not ended yet and the data on which Shodan computes trends might therefore not be complete, a small decrease in the number of iLOs in which the most common favicon is used can already be seen from the trend chart as well.

We can only hope that this trend continues in the future...

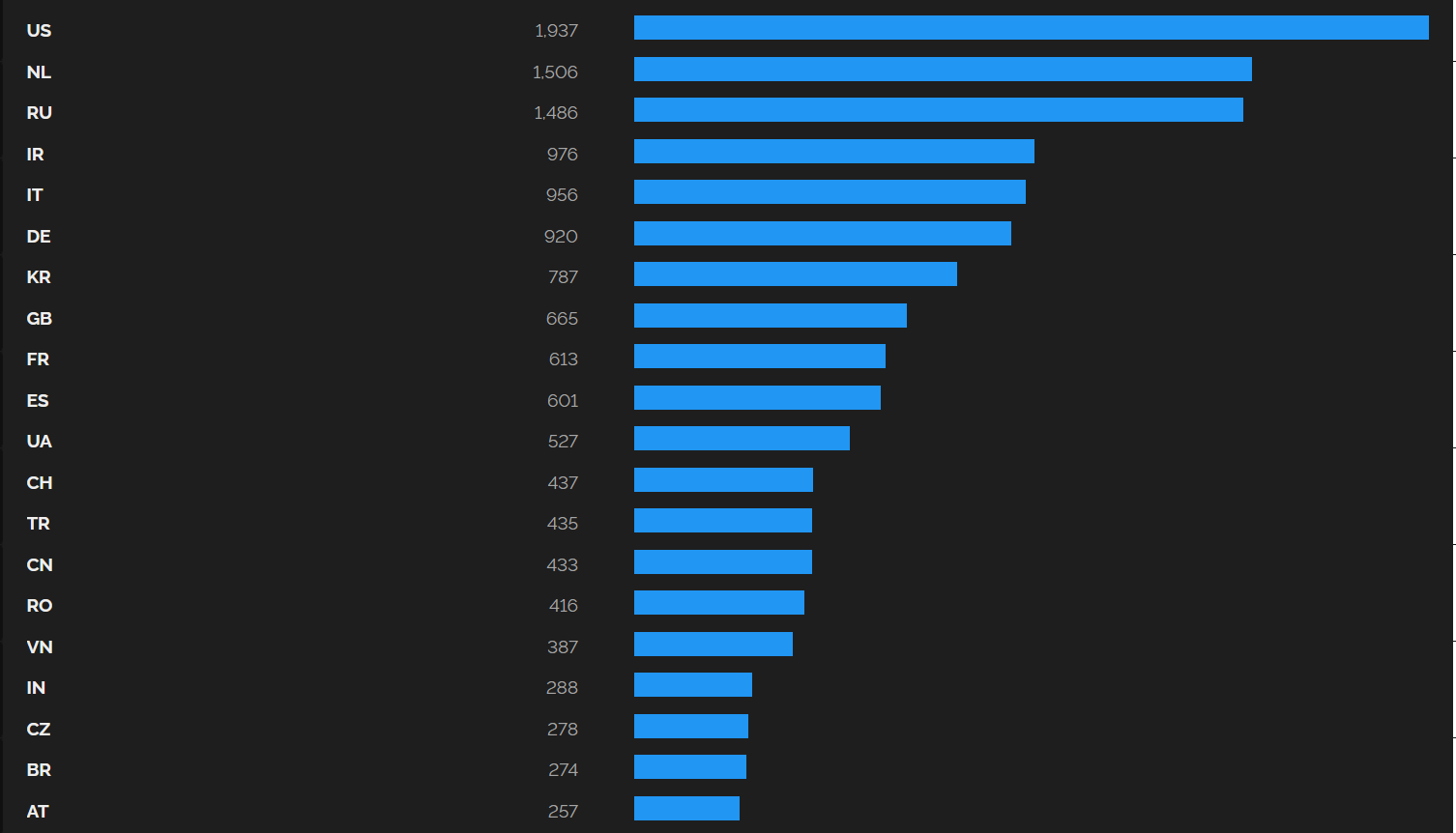

One further point which deserves a mention is the geographic distribution of identified iLOs. As you may see in the following chart, that shows 20 countries in which the most common iLO favicon was detected the highest number of times, the largest number of identified systems was in the United States, though it was not much higher than in the Netherlands or Russia. Although the inclusion of Netherlands at the top of the chart might look strange, since it has historically been one of the datacenter capitals of Europe[9], the high numbers do certainly make at least some sense.

If you would like to check whether your own public IP ranges hide any iLOs, you may use the following search strings along with the “net” operator (e.g.: “http.favicon.hash:958636481 net:192.168.1.0/24”). The third search returns 4 systems other than iLOs globally at the time of writing, all others should be false-positive-free):

- iLO 3, 4 and 5:

http.favicon.hash:2059618623

- iLO 3 and 4:

http.favicon.hash:-685753388

- iLO 4:

http.favicon.hash:-1912577989 -http.html:"Hi, I am ON from" -http.title:"latex"

- iLO 3

http.favicon.hash:958636481

- iLO 2:

http.favicon.hash:178882658

- iLO 1:

http.title:"HP Integrated Lights-Out" -http.title:"Integrated Lights-Out 2"

If you do discover any exposed iLOs in your public IP space, make sure to secure them. Otherwise, the slightly poetic name „Lights-Out“ might take on its literal meaning for your servers…

At a minimum, placing the iLO in a special VLAN with controlled access, and allowing remote access only over a VPN would certainly be a good start. But since I wanted to share some more detailed recommendations as well, I’ve reached out to the HP/HPE PSIRT and asked them for some. They responded with the following recommendation:

HPE recommends that customers follow the iLO security guidelines published at the following links:

- HPE Integrated Lights-Out (iLO) - Implementing Security Best Practices to Protect the iLO Management Interface

https://support.hpe.com/hpesc/public/docDisplay?docId=a00046959en_us&docLocale=en_US

- HPE iLO 5 Security Technology Brief

https://support.hpe.com/hpesc/public/docDisplay?docLocale=en_US&docId=a00026171en_us

If you have any HP servers with iLOs in your infrastructure, following the preceding recommendations would certainly be advisable...

Unfortunately, iLOs are only a top of the proverbial iceberg and even if we were able to make sure that all HP iLO interfaces disappeared from the internet, I’m quite sure that many other, similarly sensitive configuration interfaces would remain exposed. But if we want to change that, we have to start somewhere… And this is certainly not a bad place to start from.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HP_Integrated_Lights-Out

[2] https://threats.amnpardaz.com/en/2021/12/28/implant-arm-ilobleed-a/

[3] https://support.hpe.com/hpesc/public/docDisplay?docId=a00046959en_us&docLocale=en_US

[4] https://isc.sans.edu/forums/diary/Hunting+phishing+websites+with+favicon+hashes/27326/

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MurmurHash

[6] https://cve.mitre.org/cgi-bin/cvekey.cgi?keyword=Integrated+Lights-Out

[7] https://support.hpe.com/hpesc/public/docDisplay?docId=emr_na-hpesbhf03769en_us

[8] https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/you-can-bypass-authentication-on-hpe-ilo4-servers-with-29-a-characters/

[9] https://www.dutchdatacenters.nl/en/nieuws/dutchdatacenters2019-2/

-----------

Jan Kopriva

@jk0pr

Comments